Tweet [1]

Words matter.

When the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis reports on the United States’s capital account [2] (which it calls the “Financial Account”), one of this ledger’s two sides (interpreted to be the credit side) is labeled “Net U.S. acquisition of financial assets excluding financial derivatives” while the other of this ledger’s two sides (interpreted to be the debit side) is labeled “Net U.S. incurrence of financial liabilities excluding financial derivatives.”

This language is deeply misleading.

First, it’s inaccurate to use the singular rather than plural, as “U.S. acquisition of….” rather than “U.S. acquisitions of ….” Use of the singular gives the erroneous impression that during the stated period there has been a single acquisition of (or a single plan to acquire) assets and a single incurrence of (or a singular decision to incur) liabilities. But of course the transactions that give rise to the dollar figures that are listed on each side of the ledger of this accounting report number in the tens of thousands, perhaps even in the hundreds of thousands or even the millions. Individual flesh-and-blood people make each of these transactions, not some sentient entity called “United States.” And unlike the multitude of financial transactions carried out by business firms, these transactions are neither part of a large plan nor or meant to further the achievement of some singular goal (such as “increase the company’s – or the nation’s – net present value”).

(Indeed, many of these transactions are part of plans that are mutually inconsistent. For example, American Smith might invest in a factory in Canada the outputs of which he discovers he must sell in competition with the outputs produced by the new factory built in Texas by the Australian Jones. If Smith is very successful, he might eventually render Jones’s investment worthless; likewise, if Jones is very successful, he might render Smith’s investment worthless.)

Second – and even more misleadingly – is the description of foreigners’ investments in dollar-denominated assets as ‘Net U.S. incurrence of financial liabilities.’ This language gives the impression that each and every cent of such investments is a liability for Americans – a debt that Americans must eventually repay, or a reduction in Americans’ net financial wealth.

But the financial transactions that are recorded on America’s capital account as “Net U.S. incurrence of financial liabilities” emphatically are not necessarily the “incurrence of financial liabilities.”

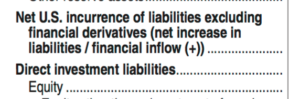

Suppose that non-American Jones uses U.S. dollars to open a steakhouse in Kansas City. This transaction is (correctly) recorded as an “Equity” investment. But here’s the detailed language used in the accounting reports:

Net U.S. incurrence of liabilities excluding financial derivatives (net increase in liabilities

Direct investment liabilities

Equity

Jones’s investment of U.S. dollars in the creation of the steakhouse in Kansas City is recorded under the “Equity” heading. This investment is indeed one of equity, but it’s not an incurrence by any American of a liability. That is, non-American Jones’s creation of a restaurant in Kansas City is wrongly listed as a U.S. liability. But it is no such thing. No American is made indebted to, or otherwise made liable to, Jones as a consequence of Jones’s creation of this steakhouse in Kansas City. If Jones’s steakhouse succeeds, Americans are richer (as is Jones). As a result of Jones’s investment, some Americans have better jobs than they would otherwise have and American diners have more or better restaurant options than they would otherwise have. The real size of the capital stock in the American economy is enlarged by Jones’s successful creation and operation of this steakhouse in Kansas City, yet no American is on the hook to repay anything to Jones.

Jones’s investment of U.S. dollars in the creation of the steakhouse in Kansas City is recorded under the “Equity” heading. This investment is indeed one of equity, but it’s not an incurrence by any American of a liability. That is, non-American Jones’s creation of a restaurant in Kansas City is wrongly listed as a U.S. liability. But it is no such thing. No American is made indebted to, or otherwise made liable to, Jones as a consequence of Jones’s creation of this steakhouse in Kansas City. If Jones’s steakhouse succeeds, Americans are richer (as is Jones). As a result of Jones’s investment, some Americans have better jobs than they would otherwise have and American diners have more or better restaurant options than they would otherwise have. The real size of the capital stock in the American economy is enlarged by Jones’s successful creation and operation of this steakhouse in Kansas City, yet no American is on the hook to repay anything to Jones.

Someone might respond by saying “Oh, but now a non-American owns the real-estate upon which the steakhouse sits – an asset that was transferred to that non-American by an American. So Americans have fewer assets.” This response is flawed.

(A) It is a mistake to infer changes in the economic well-being of the huge group “Americans” from the changes in the economic well-being of a member of this group. Even if the American Williams who sold the real estate in Kansas City to the non-American Jones is made poorer by this transaction – and even if the result of this transaction is to reduce the sum of the net worth of Americans as a group – it’s only Williams who is made poorer by his decision to sell his asset to someone else. I’m an American and I’m not made poorer. Unless I get a job at Jones’s steakhouse, in which case my financial well-being is likely improved, by well-being isn’t affected in the least by Williams being made poorer by his decision to part with an asset. Why should I care if, as the result of a voluntary transaction, a stranger to me named Jones becomes richer while a stranger to me named Williams becomes poorer? No one supposes that the offsetting financial fates of Jones and Williams affect me if both Jones and Williams are my fellow Americans, so why should their offsetting financial fates affect me if Jones is a non-American?

(B) Because the size of the capital stock isn’t fixed, non-American Jones’s acquisition of valuable real estate in Kansas City – Jones’s purchase of a valuable asset voluntarily sold to him by an American – does not imply that the person who sold that asset to him is made poorer. What does Williams, the seller of the Kansas City real estate, do with the proceeds from the sale? The answer to this question, of course, is the business only of Williams. If he chooses to spend these proceeds all on a grand one-night bacchanalia, that’s his business. But suppose that Williams invests all of the proceeds from the sale of his real estate on the development of a new smartphone app? If this investment succeeds, both Jones and Williams are financially wealthier than before. And, again, regardless of what Williams the American does with the proceeds of his sale of the asset to a non-American, neither Williams nor any other American has incurred any liability to Jones or to any other foreigner as a consequence of this transaction. Yet this transaction is reported as one that contributes to “net U.S. incurrence of liabilities.”

This language in this case is not only wrong, it is completely backwards.

“It’s only words,” you protest. “It’s mere rhetoric.” Yet words matter. People who have not studied or who have not thought carefully about international trade and investments are too easily and quite understandably misled, by reading the words used in capital-account reports, to suppose that increases in the size of the U.S. capital-account surplus (or, what is the same thing, increases in the size of the U.S. current-account deficit) are necessarily either evidence of American economic decline or sources of American economic decline (or both).

Words matter. And very misleading words are used in official documents used to report international transactions.