Tweet [1]

George Will eviscerates the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau [2]. Two slices:

Frail humans, fallen creatures in a broken world, rarely approach perfection in any endeavor. In 2010, however, congressional majorities (including [3] only six Republicans) created [4] a perfectly, meaning comprehensively, unconstitutional entity. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau [5] also perfectly illustrates progressivism’s anti-constitutional aspiration for government both unlimited and unaccountable.

…..

On Friday, the Supreme Court justices in conference will consider the CFPB’s request that the court overturn a decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit. It struck down a particular rule issued by the CFPB. The 5th Circuit argued that the rule was issued by the CFPB director while he was unconstitutionally insulated from presidential removal. And that the rule was promulgated by spending funds in violation of the appropriations clause (“No money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in consequence of appropriations made by law”).

In 2010, Congress gave a new law enforcement agency a blank check — forever. If Congress can cede funding of the CFPB to the CFPB, what limiting principle would prevent Congress from nullifying the appropriations clause by allowing the entire executive branch to fund itself in perpetuity, thereby abandoning the controlling power of the purse?

The Supreme Court should give the CFPB a reason to remember the adage “be careful what you wish for.” The court should grant the CFPB’s request and hear its challenge to the 5th Circuit. And the court should hold that the CFPB’s power to set its own budget results from Congress’s violation of the non-delegation doctrine: Congress cannot delegate to others powers the Constitution vests exclusively in it.

This is a fight constitutionalists crave. They are intellectually well-armed. Progressives have the media-academia-entertainment complex, but constitutionalists have [6] the Antonin Scalia Law School’s C. Boyden Gray Center for the Study of the Administrative State. Goliath, meet David.

My intrepid Mercatus Center colleague, Veronique de Rugy, and Christine McDaniel propose “an abundance agenda.” [7] A slice:

Unfortunately, President Biden has more or less continued to carry the protectionist torch lit by Trump, albeit a bit more diplomatically. And still these policies have yet to deliver the promised economic results. Industries given special protection via tariffs include steel, aluminum, washing machines, solar panels and a broad range of competitors with Chinese imports. Any positive effects of those tariffs for “special” sectors have come at an even bigger cost to the rest of the economy: reductions in U.S. manufacturing employment, rising input costs, higher household prices and retaliatory tariffs. Subsidies and tax credits to boost American-made semiconductors, batteries, and electric vehicles will have the same impact and will hurt the same victims.

We, of course, are not surprised by these failures, as Trump and the Nat Pops have simply exhumed the same old ghastly, desiccated protectionism that – despite insidious claims to the contrary – has never worked yet refuses to stay buried. So, rather than advocate for a return to the pre-Trump trade era, we hereby offer a more radical vision: a new dawn for America’s trading system.

Justice Antonin Scalia cautioned more than 20 years ago that Congress doesn’t “hide elephants in mouseholes.” When Congress chooses not to pursue a certain policy or delegate a new authority, it isn’t inviting administrative agencies to step in and fill the empty space. But federal agencies are increasingly attempting to impose major climate regulations with no mandate from Congress.

…..

With its recently proposed climate change policies, the Securities and Exchange Commission is similarly trying to exercise authority it doesn’t have. In an April 2022 rulemaking [10], the SEC proposed a set of expansive and costly regulations that would require public companies registered with the SEC to publish information about “climate-related risks” in annual reports and audited financial statements if those risks are “reasonably likely to have a material impact” on a company’s “business, results of operations, or financial condition.” The SEC also proposed requiring disclosure of registrants’ direct greenhouse-gas emissions as well as those from its purchases of electricity and its supply-chain partners.

This isn’t mere “disclosure.” It’s a heavy regulatory burden designed to serve climate policy goals, and it goes beyond the SEC’s statutory authority.

Climate change involves some of the biggest and most complicated policy debates of our day. A financial regulator empowered by Congress only to police fraud and protect investors isn’t equipped to engage with the policy questions surrounding climate change. That’s a mousehole of authority. There’s no room in it for a climate elephant to hide.

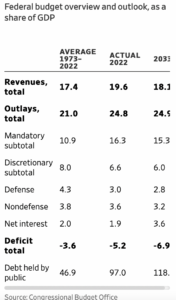

The Wall Street Journal‘s Editorial Board documents Biden’s grotesque fiscal incontinence [12]. A slice:

“What Idris Elba gets right about race [13].”

“Freedom Wins: States with Less Restrictive COVID Policies Outperformed States with More Restrictive COVID Policies” – so explain Joel Zinberg, GMU Econ alum Brian Blase, Eric Sun, and Casey Mulligan [15]. Here’s the Executive Summary (emphasis added):

The COVID-19 pandemic led to government interventions into the social and economic structures of our society that were unprecedented in their severity and duration. The fact that different states and localities took different approaches to imposing these measures created an opportunity to determine whether these interventions improved health outcomes, what economic and social side effects the interventions caused, and whether the interventions influenced people’s decisions about where to live.

This paper compares a quantitative measure of government interventions from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker—a systematic collection of information on policy measures that governments have taken to combat COVID-19—to health, economic, and educational outcome measures in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. We use the Government Response Index, which is the Oxford researchers’ most comprehensive index.

Our results show that more severe government interventions, as measured by the Oxford index, did not significantly improve health outcomes (age-adjusted and pre-existing-condition adjusted COVID mortality and all-cause excess mortality) in states that imposed them relative to states that imposed less restrictive measures. But the severity of the government response was strongly correlated with worse economic (increased unemployment and decreased GDP) and educational (days of in-person schooling) outcomes and with a worse overall COVID outcomes score that equally weighted the health, economic, and educational outcomes.

We also used Census data on domestic migration to examine whether government pandemic measures affected state-to-state migration decisions. We compared the net change in migration into or out of states in the pandemic period between July 1, 2020, and June 30, 2022, with the migration patterns over five pre-pandemic years. There was a substantial increase in domestic migration during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic trends. There was also a significant negative correlation between states’ government response measures and states’ net pandemic migration, suggesting that people fled states with more severe lockdowns and moved to states with less severe measures.

A comparison of two populous states that took divergent approaches to government pandemic measures—Florida and California—exemplifies the impact of government measures. Florida relaxed lockdowns after a short time, resulting in a low Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Index score, whereas California imposed strict and prolonged lockdowns and had one of the highest index scores in the nation. Yet the two states had roughly equal health outcomes scores, suggesting little, if any, health benefit from California’s severe approach. But California suffered far worse economic and education outcomes. And both states had substantial increases in their pre-existing domestic migration patterns. California’s severe lockdowns seemed to elicit a jump in its already high out-migration, while Florida experienced a significant in-migration increase during the pandemic as compared with pre-pandemic trends. Florida’s commitment to keeping schools open was likely a significant factor in attracting people from around the country.

This study confirms what multiple other studies have documented: Severe government measures did little to lower COVID-19 deaths or excess mortality from all causes. Indeed, government measures appear to have increased excess mortality from non-COVID health conditions. Yet the severity of these measures negatively affected economic performance as measured by unemployment and GDP and education as measured by access to in-person schooling. States such as Florida and countries such as Sweden that took more restrained approaches and focused protection efforts on the most medically vulnerable populations had superior economic and educational outcomes at little or no health cost. The evidence suggests that in future pandemics policymakers should avoid severe, prolonged, and generalized restrictions and instead carefully tailor government responses to specific disease threats, encouraging state and local governments to balance the health benefits against the economic, educational, health, and social costs of specific response measures.