In the latest issue of Foreign Affairs (HT: Fabian Franco and Nathaniel Clarkson), Kenneth Scheve and Matthew Slaughter argue that we need a New Deal for globalization. Here is the summary of the article:

Globalization has brought huge overall benefits,

but earnings for most U.S. workers — even those with college degrees — have been

falling recently; inequality is greater now than at any other time in the last 70

years. Whatever the cause, the result has been a surge in protectionism. To save

globalization, policymakers must spread its gains more widely. The best way to do

that is by redistributing income.

Here is the key empirical claim to support the proposed policy:

Less than four percent of workers

were in educational groups that enjoyed increases in mean real money earnings from

2000 to 2005; mean real money earnings rose for workers with doctorates and professional

graduate degrees and fell for all others. In contrast to in earlier decades, today

it is not just those at the bottom of the skill ladder who are hurting. Even college

graduates and workers with nonprofessional master’s degrees saw their mean real

money earnings decline. By some measures, inequality in the United States is greater

today than at any time since the 1920s.

I didn’t see a source for this claim about different educational groups. I assume it’s true. But three things trouble me about it.

The first is most people would have trouble telling you whether their real income today (or in 2005) is higher than it was in 2000. Most people have higher nominal income. They are unlikely to have a precise idea of the rate of inflation over five years. So unless they look the number up, they’d have trouble giving an accurate assessment of their economic progress over their five years. So I’m not sure that the income numbers of the last five years are creating a political backlash against immigration.

Second, I think most people would have an opinion about how OTHERS have done over that five year period. I think most people think other people are falling behind even if the person answering the question is doing fine. They are pessimistic about others because that is what they hear over and over again—that most people are doing badly. They hear it from the press. They hear it from many politicians.

Third, and this is the most important point, money income is deceptive in a world of expanding fringe benefits.

If your money income, corrected for inflation, stays constant, but your health care benefits rise to cover the rising cost of health insurance, in recent years, you are better off. Why? The increase in your health care benefits just cancels out the increase in health care costs, but those costs are included in the deflator used for money income. So in fact, you have more purchasing power–your real income has increased. I didn’t say that so well. Here’s a better way to see it, from analysis by Gary Burtless:

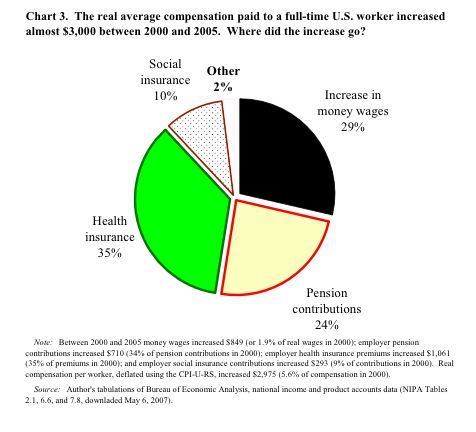

I’m not sure you can read the figure but here’s the gist of it. Between 2000 and 2005, compensation for the average worker rose $3000. But money income was only 29% of the increase. The bulk of the increase was in non-monetary compensation—increases in health insurance, pension contributions and taxes for social security.

Instead of finding ways to save globalization with redistribution, maybe we should try educating people about how labor markets work and the importance of fringe benefits.

Of course, these numbers from Burtless are average numbers. It’s still possible that a lot of people didn’t see their standard of living improve between 2000 and 2005. But it’s also clear that just looking at money income is only part of the picture.