American capitalism supported decades of innovation that created conditions conducive to the rapid development of the Covid vaccines. About 70% of the returns to medical research and development across the world come from the U.S., where price controls are less prevalent than elsewhere and companies compete to bring new treatments and cures to market. Without the U.S. market, investors would have shied away from funding the cumulative advances that eventually led to successful Covid vaccines. In this sense, the U.S. market-based healthcare economy saved the world from Covid-19. None of it would have happened in a government-run health system.

…..

Markets may fail sometimes, but government policy fails much more frequently, and the world benefits from private efforts to mitigate the fallout from those failures. The almost universal view of economists that government policy serves to correct market failures is misguided.

Speaking of government failure, Eugene Volokh shares this e-mail, originally sent to a listserv, from LSU Law professor Ed Richards (emphasis added by Boudreaux):

This is a comment about Louisiana, although it applies in varying degrees to other states.

If you are a historian of hospitals in the US, or just an old health policy person, you know that post-WWII the federal government subsidized the construction of a lot of hospitals and created the expectation that every small town would have its own hospital. In the 1970s, health economists raised questions about the costs of running hospitals at 40-50% occupancy. This led to the passage of PL 93-641, the health planning act, and the Certificate of Need Program (CON). CON was intended to have community boards vet new hospital beds, etc., with an eye to reducing costs in the community by reducing excess capacity. CON was mostly a bust—everyone understood in theory why excess beds were a problem, but no one wanted to forgo a new facility in their community.

Market changes did what CON didn’t and over the next 30 years squeezed out excess beds so that hospitals could operate at 90% capacity and make a lot more money. It was recognized at the time at time this was also removing the excess capacity that was a buffer for when there was a bad flu season or other outbreak. After 9/11 and SARS1, there were plans to build emergency ICUs outside of hospitals during outbreaks, including tents in the parking lots, to make up for the loss of beds. These plans were based on the assumption that there would plenty of people who could be brought in to staff the beds—sort of misunderstanding the PAN in pandemic.

Louisiana was a leader in the specialty hospital business, having neither an effective CON process or state regulatory system. The public argument for specialty hospitals is more expertise and lower costs because of efficiency. The real model was no emergency room, and thus no way for un- and under-insured people to get into the hospital. All of the financial benefits of being a hospital without any of the responsibilities. So we get women’s hospitals, orthopedic hospitals, etc., sucking the profitable work from community hospitals, without taking any of the burden of community care for the indigent. General hospitals are even allowed to close their ERs in Louisiana.

The hospitals in Louisiana which take indigent patients and patients though the ER—pretty much all COVID patients—are slammed. The specialty hospitals have lots of staff and lots of beds and don’t have much in the way of COVID patients, if there are any at all. They also do little to help the others. Thus Louisiana has a very small number of general beds that are available for COVID patients. It is a real crisis, but it is as much a crisis in health care resources as in COVID. While the Children’s hospitals do have ERs, there are not many of them in Louisiana and there are very few total ICU beds. As another list member observed, you can have all the pediatric ICU beds full and still only have a tiny number of kids who are very sick.

Patrick Barron’s letter, in the Wall Street Journal, on the eviction moratorium is spot-on:

In his book “Economics in One Lesson,” Henry Hazlitt states that we must look not only at what is seen but also at what is unseen. A corollary is to look not only at the short-term effect but also at the long-term effect. The unseen effect here is financial cost to landlords. The long-term effect is on the willingness of landlords to stay in the business and provide rental housing in the future. There’s no such thing as a free lunch.

Patrick Barron

West Chester, Pa.

Robby Soave rightly bemoans the spread of yet more misinformation about Covid. A slice:

A viral Instagram post claimed that COVID-19 is 99 percent survivable for most age groups—the elderly being an important exception. The post cited projections from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), but was flagged as misinformation by the social media site and rated “false” by the Poynter Institute’s PolitiFact.

That’s a curious verdict, since the underlying claim is likely true. While estimates of COVID-19’s infection fatality rate (IFR) range from study to study, the expert consensus does indeed place the death rate at below 1 percent for most age groups.

Sunetra Gupta defends herself against unfair charges.

The next morning, Mayor Bill de Blasio injected himself into that private dialogue. Under his vaccine-passport mandate, we must immediately submit to the vaccination of our son and 15-year-old daughter, or they will be treated as second-class citizens in New York City. They will be prohibited from entering restaurants and movie theaters, attending most indoor events or, in de Blasio’s words, generally living “a good and full and healthy life.” (They may continue to live a good and full and healthy life across the county line in our suburban village, not to mention everywhere else in the U.S.)

Americans are significantly divided, along party lines, on the question of ‘vaccine passports.‘

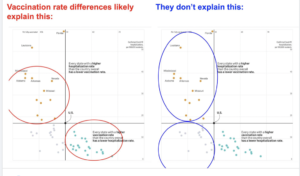

Phil Magness offers with this picture a lesson on the danger of (mis)interpreting data points:

Adam Creighton rightly criticizes Bill Gates’s express admiration for Covidocratic tyranny.

I’m glad that a court ruled against Florida governor Ron DeSantis on this particular matter.

Jonathan Ellen decries the unrealistic expectations and disproportionate response to Covid. A slice:

The panic stems from a failure to ask basic questions. Are our leaders setting realistic policy goals? Have they put too much emphasis on eliminating Covid-19? Is there any historical precedent for the rapid completion of a vaccination campaign?

These days, Americans tend to demand that societal problems be 100 percent fixed as soon as they’re discovered. When they’re not, media outlets explode with dire warnings and moral outrage. Not surprisingly, politicians and policymakers respond to this panic, failing to maintain a realistic perspective on what’s possible and what’s not.