One my dearest friends would, were he still alive, today turn 100. Hugh Macaulay was born on May 17th, 1924, in Seneca, South Carolina. After serving in the U.S. Army in WWII (and being injured), he earned his PhD in economics at Columbia University. Below the fold is the tribute I wrote for Hugh on October 19th, 2005, the day that he died.

One my dearest friends would, were he still alive, today turn 100. Hugh Macaulay was born on May 17th, 1924, in Seneca, South Carolina. After serving in the U.S. Army in WWII (and being injured), he earned his PhD in economics at Columbia University. Below the fold is the tribute I wrote for Hugh on October 19th, 2005, the day that he died.

My and Karol’s very dear friend Hugh Macaulay passed away this afternoon, following a brief illness. He was 81.

Hugh was an economics professor at Clemson University until his retirement in 1983. He had to retire early because he suffered macular degeneration, a disease that blinded him.

Karol and I met Hugh and his wife, Pinky, in 1992 when I joined the Clemson faculty. Although they were half-a-generation older than our parents, we immediately became very close friends with the Macaulays. The reasons are countless, but they include the Macaulays’ immense decency, and Hugh’s unquenchable thirst for learning ever-more economics, and his and Pinky’s deep love of liberty.

I have never met anyone who takes such a sincere interest in other people as Hugh Macaulay took. Almost every week between 1993 and 1997, Hugh and I met for lunch at the Ramada Inn in Clemson. Hugh asked every waiter or waitress, every bus boy, who came to our table about their day. “How are you today, Bill?” Hugh would ask — ask not nosily, not noisily, not condescendingly, not officiously, not ostentatiously; simply sincerely.

Every one of these people loved “Mr. Macaulay” because of his genuine concern for them.

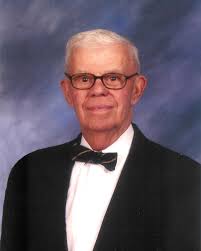

Hugh’s physical stature was on the small side. He dressed nattily, almost always wearing a bowtie. He was forever alert, always smiling, always praising others. I can still see him nodding his head, telling someone with us at lunch or at our monthly book-club meeting that “that’s a goooodddd idea!!”

And Hugh found lots of ideas to be good. At first, I thought he was just being kind when he expressed his admiration for some idea that struck me as mediocre, for I knew that he easily and immediately perceived the difference between ideas that are banal and those that are worthwhile.

But I learned that Hugh possessed that too-rare quality not only of interpreting each person’s statements in the very best light possible, but also of extracting genuine insights from others’ statements even if those of us who uttered these statements never realized the depths of our insights until Hugh explained them to us.

Hugh’s favorite economist was Ronald Coase. And Hugh was Coasean to the bone. His grasp of the importance of transaction costs and of the wide range of, and promise of, bargaining opportunities was awe-inspiring. Hugh truly was a natural economist; he could not not ask “as compared to what?”; he could not not be alert to unintended consequences; he could not not understand that all decisions take place at the margin.

Hugh could not help but be a superb economist.

Like many superb economists, Hugh did not write much. But he taught with masterful skill and devotion. I’ve met dozens of his former students, each of whom credits Hugh with inspiring him to learn economics, and to think like an economist. And although I was never his student in the formal sense, I was, since the day I met him, Hugh’s devoted and grateful student informally. I can’t begin to measure the value of the cornucopia of insights that I learned from Hugh Macaulay. Every conversation, without fail, taught me something worthwhile.

Hugh and Pinky were such dear friends that Karol and I named our only child in their honor; he is Thomas Macaulay Boudreaux. It’s a pleasant bonus that this name recalls also the great English essayist and historian. But our son boasts the middle name of ‘Macaulay’ because of Hugh and Pinky. I fervently hope that he grows up to be a man, a human being, worthy of his namesake.

Good-bye, Hugh, my dear, dear, dear friend.