In his April 16th Wall Street Journal column, William Galston writes:

Between 2001 and 2007—before the financial crash and the Great Recession—the U.S. lost 3.4 million manufacturing jobs, almost 20% of the 17.2 million manufacturing jobs we had at the end of 2000. During the recession, another 2.2 million manufacturing jobs disappeared. In the ensuing 15 years, the economy regained barely one-fifth of the manufacturing employment lost during that first decade of the 21st century. This was the famous “China shock,” which helped trigger the populist revolt that later brought Donald Trump to power.

Economists continue to debate the relative contributions of China versus productivity-enhancing technology in destroying so many manufacturing jobs. Technology certainly made a difference; manufacturing productivity increased significantly between 2001 and 2010. But productivity increased almost as much between 1991 and 2000, when the number of manufacturing jobs was generally increasing. The major difference between these decades was China.

If you click on the link in the first-quoted paragraph above, you will indeed notice a sharp acceleration in the decline in the absolute number of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. starting in early 2001 – at which time the U.S. economy slipped into a mild recession. This decline continued apace until early 2004, when it significantly slowed. (That graph, showing monthly manufacturing-employment numbers as far back as January 1939, also shows that the absolute number of manufacturing jobs always sharply declines during recessions. The only possible exception is the mild and brief downturn in the early 1990s when the decline in the absolute number of manufacturing jobs, although real, did not accelerate sharply.)

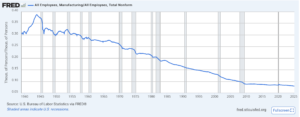

But data on the absolute number of manufacturing jobs are less relevant and informative than are data on manufacturing jobs as a share of total employment – or, more precisely, as a share of all nonfarm jobs. (You can, as I did, find these data by dividing the St. Louis Fed’s data on the absolute number of manufacturing jobs [MANEMP] by data on all nonfarm jobs [PAYEMS].) Here’s a screenshot of these data (from January 1939 through March 2025).

Notice that, over the time period singled-out by Galston – China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) (December 2001) until the start of the Great Recession (December 2007) – there is no apparent acceleration in the decline of manufacturing jobs as a share of total nonfarm employment.

Appearances here aren’t deceiving. I calculated the average monthly percentage decline in manufacturing jobs as a share of total nonfarm employment over Galston’s six-year period (December 2001 through November 2007) as well as for the exact same number of months immediately prior to that period (December 1995 through November 2001). From December 2001 through November 2007, manufacturing jobs as a share of total nonfarm employment fell at an average monthly rate of 0.268 percent. From December 1995 through November 2001, manufacturing jobs as a share of total nonfarm employment fell at an average monthly rate of 0.260 percent.

In short, over the seven years from China’s entry into the WTO until the start of the Great Recession, the average month decline in the share of manufacturing jobs as a share of all nonfarm jobs was pretty much the same as it was over the equally long time period leading up to China’s entry into the WTO.

…..

For what it’s worth, the post-WWII post-1948 high of manufacturing jobs as a share of total nonfarm employment occurred in May 1953, when it was 32.3%. Today (March 2025) it’s 8.0%. From May 1953 through November 2007, manufacturing jobs as a share of all nonfarm jobs fell at an average monthly rate of 0.18%. From December 2007 through March 2025, manufacturing jobs as a share of all nonfarm jobs fell at an average monthly rate of 0.10%. That is, for the past 17-plus years, the decline in manufacturing jobs as a share of total nonfarm employment has slowed.

Make of this fact what you will. Because I don’t believe that there’s anything especially economically meaningful about manufacturing as opposed to non-manufacturing economic activities – and because I understand that in an economy as large and dynamic as that of the U.S. there are lots of changes incessantly occurring – I don’t make much of this fact one way or the other. But those people who interpret the loss of manufacturing jobs as both an alleged reason for the rise in the U.S. of protectionist sympathies and as a justification for protective tariffs should at least be asked this question: Why did MAGA protectionist fervor explode on the scene only after the rate of decline in manufacturing jobs as a share of total employment slowed?