History may not perfectly repeat itself, but it often rhymes. Two protectionist episodes — the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 and the Trump-era tariffs of today — offer a striking example. Both emerged from economic nostalgia and fear of change. Both were politically attractive. And both were costly, backward-looking mistakes that undermined the economies they were meant to protect.

Smoot-Hawley was conceived in an America uneasy about economic transformation. In the 1920s, while the economy was otherwise booming, farmers were in crisis. After a postwar boom, crop prices had collapsed and rural debt soared. About one-quarter of the labor force still worked in agriculture, down from one-half a few decades before. Many Americans longed for an earlier era when agriculture was dominant and prosperous.

Foreign competition was the scapegoat. Politicians seized on this frustration. Promising protection from cheap imports was an easy way to win votes. The result was a tariff that raised duties on more than 20,000 goods by an average of about 20%.

Smoot-Hawley’s intent was to reduce imports and raise domestic prices, especially for farmers. But the plan backfired quickly.

…..

The two blunders have one more thing in common: cronyism. According to economic historian Douglas A. Irwin, Smoot-Hawley was not primarily about ideology. It was about interest-group politics: an ad hoc scramble driven by constituent demands, sectoral lobbying and legislative bargaining.

In the same way, Trump’s tariffs have revived the lobbying for tariff exemptions we saw in his first term. Apple got an exemption for the iPhone and now, understandably, everyone else wants one. As the Cato Institute’s Scott Lincicome on X, “The cronyism buffet line is now open.” National Review’s Dominic Pino calculated that tariff lobbying spending is up by 277%.

The lesson is clear: Economic nostalgia is a poor guide to sound policy. Smoot-Hawley and Trump’s tariffs represent attempts to re-create a romanticized past — one of small farms or bustling factories — rather than to embrace the reality of a changing world. But economies are dynamic. Trying to freeze them in place with trade barriers doesn’t stop change; it just makes the transition harder, costlier and more painful.

David Henderson eloquently clears the air on trade deficits and tariffs. Two slices:

First, is a trade deficit with a particular country bad? No. One of the easiest ways to see that is to look at your own spending on other producers’ goods. Consider mine. Our household spends over $5,000 a year on groceries from Safeway. But those scoundrels at Safeway spend nothing on my output. If you’re employed, your employer has a trade surplus with you. He or she spends much more on your services than you spend on his products. But that’s not a problem.

The same reasoning applies to a specific country. Our trade deficit with Canada in 2024 was about $36 billion, not the $100 billion that President Trump seems to have pulled out of thin air. And contrary to Trump’s belief, the fact that we spend more on imports from Canada than Canadians spend on our exports does not mean that we’re subsidizing Canadians, any more than I’m subsidizing Safeway. There’s no reason that we should have a zero trade deficit with a particular country. In 2024, the United States had trade surpluses with the Netherlands ($56 billion), Hong Kong ($22 billion), Australia ($18 billion), and the United Kingdom ($12 billion). Was that a problem for those countries? The heads of those countries and, apparently, many of their citizens, don’t seem to think so. It’s very much like you having a trade surplus with your employer.

…..

Imagine, contrary to the data, that every country’s government in the world imposes higher tariffs on our exports than the US government imposes on our imports. What would be the best strategy for our government?

The answer may shock you, but I assure you that my answer is based on decades, nay centuries, of economic reasoning and evidence. The answer is: cut our tariffs to zero.

Why? It’s true that when a foreign government imposes tariffs on our exports, it hurts our producers. It also hurts the foreign government’s consumers. If our government responds by imposing tariffs on imports from that country, it helps our producers who compete with those products but hurts our buyers of those items. Those buyers include not just ultimate consumers, but also producers who use the tariffed items as inputs. It’s relatively easy to show, although you need a graph of supply and demand, that the losses to our consumers exceed the gains to our producers.

The bottom line, therefore, is that whatever the other country’s government does, our government’s best option, if it puts the same weight on losses to consumers as it puts on gains to producers, is to have zero tariffs.

Two major figures in the last century used metaphors to make the point. One was President Reagan. In the early 1980s, he argued that if you’re in a lifeboat and someone shoots a hole in the boat, it’s not a good idea to shoot another hole in the boat. Yes, you’ll hurt the first shooter; but you’ll also hurt yourself.

The other was famous British economist Joan Robinson. If someone in another country to which you ship goods puts rocks in the harbor to make shipping more difficult, she asked, does it make sense for you to put rocks in your harbor?

…..

Fear of trade deficits comes from atavism and tunnel vision.

The atavism is the lingering faith in mercantilism, whose medieval proponents loved the export of tangible goods and despised imports. Their economic ideal was to sell exports and accumulate idle hoards of gold. (Think of Scrooge McDuck diving into his swimming pool full of coins.) David Hume, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and others revealed the fatal flaws in this philosophy by showing how trade is mutually beneficial for both importing and exporting countries. Imported goods bring both satisfaction to consumers and inputs with which investors can generate future wealth. Because of this latter factor, there’s no limit to how long a nation can run a trade deficit.

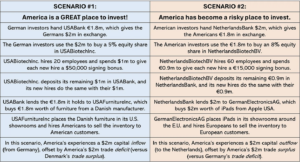

The tunnel vision is the tendency to focus on narrow segments of the economy and ignore the rest. In the deficit/surplus example above, mercantilist nostalgia might—pun intended—pine for the loss of some furniture-making factories in America and long for them to come back. But mercantilism (currently traveling under the moniker of “anti-globalism”) ignores the other parts of the story. In the example above, mercantilists remember bygone American furniture factories but fail to notice the willingness of foreigners to invest in America, the rise of new American industries like biotech, the high-paying jobs these new industries bring, the wealth those new industries create as their newly wealthy employees buy furniture and cars and healthcare, and the capacity of Americans to consume and invest in magnitudes unimaginable to their parents or grandparents.

…..

“Globalism” (a.k.a., free trade) is to those on the political right what “trickle-down economics” (a.k.a., free markets) is to those on the political left. Both are vacuous pejoratives that translate loosely into English as, “Somewhere on Earth, buyers and sellers are engaging in voluntary trade and minding their own business AND WE HAVE TO STOP THEM.”

GMU Econ alum Dominic Pino elaborates on “Trump’s impossible trade policy.” Two slices (ellipses original to Dominic):

When other countries subsidize production or “dump” goods into the U.S. market, they are taking money from their people to make things cheaper for our people. From a purely nationalistic point of view, that seems like a good deal. Even if you think this is a problem, broad tariffs won’t solve it. There are a bunch of international trade rules about subsidies and dumping and U.S. laws that allow antidumping duties on specific goods after an investigation. The U.S. could bring a bunch of cases before the WTO and use the antidumping law it already has if Trump really wants to stop this “cheating” of . . . receiving more affordable goods from abroad.

…..

There is no sophisticated plan to negotiate great trade deals or reduce other countries’ trade barriers behind the Trump administration’s chaotic implementation of its signature economic policy. The task it has set for itself is impossible, which is likely why it hasn’t really attempted to do it, instead settling for a simple formula based solely on the volume of imports and the size of the trade deficit. These facts will not be any different in early July when the tariff pause is set to expire.

The Editorial Board of the Wall Street Journal wonders if this is “Trump’s Mitterand moment.” A slice:

President Trump continues to walk back his original tariff assault, and markets are pleased. They rose again Wednesday after Mr. Trump said he won’t fire the Federal Reserve Chairman and is likely to retreat from his highest China tariffs. Is this Mr. Trump’s François Mitterrand moment?

Readers of a certain age will recall how the French Socialist President swept into power in 1981 promising a far left agenda of government control over the private economy. The market reaction was brutal. Within a year he had put socialism on pause and by 1983 he had abandoned most of it. He went on to serve two terms.

That historic U-turn comes to mind as we watch Mr. Trump execute a reversal by stages in his tariff agenda. First he carved out space for Mexico and Canada from his reciprocal tariffs. Then he put his reciprocal tariffs on everyone except China on a 90-day pause. Then the Customs bureau gave exceptions to Apple, Nvidia and big electronics companies. Now comes word that Mr. Trump may substantially cut his 145% tariff rate on China.

That’s a long way in three weeks from the declarations by White House aide Peter Navarro and Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick that there would be no tariff-rate changes. It’s hard to see this as anything other than a retreat amid the harsh reaction of financial markets, worries about recession and price increases, and a sharply negative reaction from the rest of the world—friend and foe.