In a briefing paper published last year, economist Fariha Kamal explained that “half of all U.S. imports are industrial supplies and capital goods . . . used as intermediate inputs by manufacturers.” Put another way, American manufacturers use a lot of foreign components or equipment. That’s so they can produce competitively priced goods for buyers at home and, incidentally, abroad. Manufacturers which import tend to be significant exporters too, but that doesn’t appear to impress the tariff Taliban.

Slap a tariff — or let’s call it what it is, a tax — on American manufacturers’ inputs, and their costs will rise. They may try to pass the increase on to their customers if they can, but they may also try to secure supply lines in the U.S. in order to avoid the tariffs. That’s what the tariff-setters want, they say (at least when they are not boasting about how much money they will make from their tax, something that implies American companies and consumers will not find satisfactory substitutes), because that will mean that sub-suppliers in the U.S. secure more business, employ more workers and so on.

Phil Magness shares evidence that “America hates the Trump-Vance tariff agenda.”

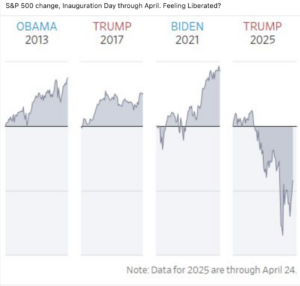

Mark Perry shares evidence that the Trump-Vance tariff agenda is hated also by investors:

N. Gregory Mankiw, professor of economics at Harvard University, tells Reason the most important takeaway from the declaration is that “economists are really united in opposition to the Trump international economic policy, [which] seems to be founded on a variety of very fundamental misconceptions about economics and economic history.”

Michael Munger, professor of economics and political science at Duke University, says he signed because “tariffs are bad domestic policy, and bad foreign policy.” Munger explains that the argument for free trade is unilateral: “If another country manipulates its currency, or has trade barriers, that is a harm to THEIR consumers. ‘Wealth’ is the ability to obtain high quality, low cost products.”

…..

Henderson also acknowledges that the declaration will not have a huge effect right away but, “even if the effect is small, it will be in the right direction.”

Nonetheless, Mankiw believes it’s useful for the world to know when the economic profession has a consensus and for economists to speak with one voice when they can. Benjamin Powell, professor of economics and executive director of the Free Market Institute at Texas Tech University, agrees with Mankiw. He tells Reason that the Trump administration’s haphazardly imposed tariffs are “completely at odds with the standard mainline understanding of virtually all professional economists.”

GMU Econ alum Dominic Pino reports that “Congress can stop the tariff madness next week.” A slice:

Many members of Congress are uncomfortable and concerned about the impacts of tariffs in their districts and states. Trump’s economic-approval ratings have declined over the course of the month, and that decline is bleeding over into other issues such as immigration. The bond market continues to send troubling signals about investors’ confidence in the U.S., which is partly due to the massive uncertainty in the entire country’s trade rules.

Republicans in Congress can complain about all of this. They can continue to field calls from retirees in their districts about the value of their IRAs being depleted and from business owners in their districts about the jobs they’ll have to cut and prices they’ll have to raise because of tariffs. Republican lawmakers will then face the consequences when voters go to the polls next year, with Democrats now leading in the generic congressional ballot.

Or, they can vote for this resolution next week and end this sideshow. Republicans need to focus on cutting spending and extending the 2017 tax cuts, and all the political capital that is burned on this nonsensical tariff policy can’t be used for those vital tasks.

Wonderstate Coffee imports its coffee primarily from Peru and Ethiopia in addition to Mexico, Colombia, Honduras, Kenya, and other countries with a warmer climate. There are very few coffee farms in the U.S., with the exception of those in Hawaii, California, and Puerto Rico, so the coffee industry relies heavily on international trade for its goods.

The Trump administration kept in place the base 10 percent tariff on every country from which Wonderstate Coffee receives imports. Even roasted coffee from Mexico faces a direct hit from tariffs, as it is noncompliant with the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement.

The tariffs threaten the company’s ability to grow, pay its staff, and invest in new equipment, adding to the existing challenges of labor shortages and rising business costs that small businesses often face.

…..

Domestic manufacturing more broadly has been negatively impacted by the downstream effect of tariffs, with thousands of factory workers having been laid off so far. While Trump claims tariffs are meant to bring jobs back to the U.S., manufacturing workers are more convinced than not that tariffs will hurt their jobs and careers.

Richard Swanson’s letter in today’s Wall Street Journal is spot-on:

Mr. [Gerard] Baker focuses on how President Trump has bungled the execution of his objectives, not his targets. But he had bungled those too. The president targets German, Korean and Japanese cars, even though consumers like them. He targets Google, but consumers like the efficiency of its search engine. He targets Uber, but consumers like its on-time rides over the old taxi monopolies. He targets the Federal Reserve over interest rates, but consumers hate inflation. He targets Chinese, Indian and Vietnamese mercantilism, but consumers like affordable goods.

In short, targeting consumer preferences is akin to shooting one’s own foot, even if firing the gun is executed to perfection.

The Trump Administration wants to promote U.S. tech innovation and competition. Then why is it fighting rearview antitrust battles that would do the opposite?

…..

The government wants to force Google to divest its Chrome browser to degrade its ability to target ads. This would hurt advertisers while helping other companies that serve up ads such as Amazon and Meta. DOJ also wants to require Google to share search data with competitors like Microsoft and OpenAI.

DOJ says the judge should ban Google from paying for default placement on browsers and devices. Even Mozilla, a browser competitor to Google’s Chrome, said the government’s “misguided plans would be a direct hit to small and independent browsers—the very forces that keep the web open, innovative and free” and primarily benefit Big Tech companies like Microsoft.

Meanwhile, antitrust regulators are investigating Microsoft and OpenAI. Would the real monopolist please stand up?

For consumers today, there is a wide array of social media platforms to connect and communicate with friends, family, and the general public. This includes platforms both owned by Meta and those that are not. The FTC’s market definition does not recognize this reality and instead seeks to define “personal social networks” so narrowly that it excludes popular online products like TikTok. This does not reflect the reality of the consumer experience, especially when considering trends among Gen Z users.

But why should consumers care if Meta has to split off from Instagram and WhatsApp? Well, it might make their experiences on those platforms worse. A court-ordered breakup would also likely create requirements that prevent things like cross-posting or messaging interoperability. This could also eliminate certain products consumers like. For example, what if Meta were faced with the choice of keeping only Messenger or WhatsApp?

Trump did get this call on tax policy right:

President Trump disappointed Democrats this week when he wisely rejected the idea floated by some on the right to raise tax rates on high earners. He’s saving Republicans from a blunder that would divide his coalition and hurt the economy.

Our Kimberley Strassel reported last week that leaks in support of raising taxes are coming from political allies of Vice President JD Vance. Steve Bannon, the Goldman Sachs-Hollywood populist, has pitched letting the top rate revert to 39.6%—the level before the 2017 tax reform—from 37%. That rate now begins at $626,350 in income for individuals. He and others also want new tax brackets for those earnings more than $1 million, and perhaps $3 million or $5 million.

Liberals [DBx: ‘progressives’] cheered the idea, but Mr. Trump knocked it down Wednesday. “You’ll lose a lot of money if you do that,” the President told reporters. “And other countries that have done it have lost a lot of people. They lose their wealthy people. That would be bad, because the wealthy people pay the tax.” He’s right on all counts.

Juliette Sellgren talks with my former GMU Econ colleague Bart Wilson about humanomics.