Surrounded by airline CEOs and other aviation executives, Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy on Thursday announced his plan to bring about a new air-traffic control system over the next three to four years. He’s asking Congress to provide billions of dollars—though he didn’t specify the total amount—to pay for it.

America’s ATC system needs repairing. Most of the technology listed in Mr. Duffy’s plan should be replaced. But shoveling billions into a failed procurement system won’t fix the problem. Our ATC system lags behind those of other countries in many respects, including in technological advancement and productivity.

The Federal Aviation Administration’s budget for facilities and equipment—a substantial portion of which goes to air-traffic control—has stayed roughly flat in nominal terms over the past decade, while the operations budget has soared. The 21 high-altitude air route traffic control centers, more than 100 approach control centers, and many hundreds of airport control towers are antiquated, and most need to be replaced.

But with today’s digital surveillance technology, air traffic in our skies can be managed from almost anywhere. We need perhaps three rather than 21 high-altitude centers. One would do the trick, in fact, but three would ensure backup options in case of failure. This large-scale consolidation should be financed by long-term revenue bonds based on ATC user fees, which are paid by airlines and other airspace users to the ATC service provider. A pipe dream? Australia, Germany, South Africa and the U.K. have all done such consolidations in recent decades.

A single digital remote tower can manage many smaller control towers, at lower cost and higher productivity. While these systems are expanding throughout Europe, the FAA has resisted this breakthrough innovation.

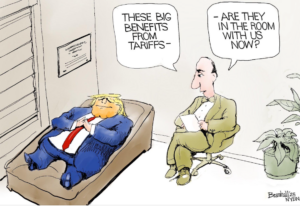

Eric Boehm is correct: “The U.K. trade deal screws American consumers.” Two slices:

The agreement maintains the 10 percent universal tariff that President Donald Trump imposed on nearly all imports to the United States. But even the president admits this is a tariff hike on American consumers, rather than a reduction.

The point of comparison should be the average tariff rate on imports from the U.K. before Trump took office. In 2023, the most recent year for which full data are available, the average U.S. tariff on British goods was 3.3 percent.

That means this “deal” charges American consumers a 10 percent baseline tax on goods that were previously taxed at 3.3 percent. That’s not a win for free trade or lower prices.

…..

In other words, the “deal” means tariffs on British cars have been quadrupled for American buyers. That’s hardly a win for Americans.

If the agreement with the U.K. was supposed to demonstrate that Trump is a master dealmaker who is wielding tariffs to bend the global economy toward Americans’ best interest, it falls well short.

Trump and his advisers claim that their policies have three justifications. For simplicity, I will call these (1) security, (2) reciprocity, and (3) revenue. I’ll present these (as the lawyers put it) arguendo, meaning that for the sake of argument, we will just consider the case for Trump’s actions, and mostly put aside the counterarguments.

…..

The problem for Trump supporters is that even if one grants that each argument has some merits on its own, the three together are an incoherent and highly destructive muddle.

The security argument implies, and in fact requires, that the US must permanently set up industries to make things that it could buy more cheaply on international markets. In particular, tariffs need to be high and fixed forever to block the import of foreign semiconductors, ships, and whatever else security demands. Only if there is a credible commitment to permanent confiscatory tariffs will domestic industries invest in the capacity to make these products, since by definition other countries can make them more cheaply than we can.

Fair enough, but then high tariffs cannot be used as a bargaining chip in reciprocal negotiations, and tariffs cannot be low enough to earn revenue. After all, the only way tariffs produce revenue is if they are low enough as to not discourage substantial imports, and that is the opposite of the stated goals. The security argument requires no imports, no negotiated tariff reductions, and no revenue, because trade itself is the danger. The security argument, if it is correct, rules out the reciprocity argument and the revenue argument.

…..

Finally, the revenue argument requires that there is little change in the volume of trade. Low, across the board tariffs would be necessary to avoid the substitution of products from adversary nations such as China to neutral countries such as India or the nations of Southeast Asia. Since the only way to make money from tariffs is to have them low enough as to not to discourage imports, the security argument is entirely precluded, and no domestic producers will invest in US capacity.

Not only are jobs growing, but job growth has outpaced population growth—i.e. the increase in the number of people available to fill those jobs—and this has been the case for most of the last four decades.

GMU Econ alum Jon Murphy reveals some hidden ill-consequences of tariffs. A slice:

There are many ways for firms to adjust to tariffs, not all of them are raising prices. Walmart is reducing employee benefits. Some firms are considering cutting product lines. Firms are overstocking now. In another WSJ article, other firms are cutting employee benefits like travel. All of these are real costs over and above the loss in consumer welfare and deadweight loss from the tariffs.

Yep. (HT Tom Palmer)