The intrusion of fundamentally anti-conservative ideas into American conservatism is connected to the rise of illiberalism on the left. For over a decade now, “wokeism” has produced authoritarian groupthink — genuine cancel culture — in universities, in journalism, in law and business firms, in medical education and practice, and in the public square as a whole. Decent and honorable people lost educational and professional opportunities, jobs, careers, financial stability and reputations when left-wing outrage mobs came for them. Illiberalism laid the groundwork for the “groyper” backlash now in full swing.

Still, the reality is that although these bigots are an extremely noisy online presence, most conservatives, including plenty of young conservative men, still embrace what Abraham Lincoln called the “ancient faith” — the principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. By embracing these principles, conservatism can meet today’s political, cultural and economic challenges.

Mario Loyola and Derrick Morgan plead for the Environmental Protection Agency to “break the ethanol habit.” Two slices:

Gasoline prices are down, but the Environmental Protection Agency is about to push them up. President Trump is committed to affordable energy, but he is also under intense pressure from the corn-state ethanol lobby.

Ethanol in the U.S. is a $34 billion industry created by a hidden federal subsidy: the Renewable Fuel Standard, or RFS, a mandate that oil refineries blend a certain total amount of ethanol into the U.S. gasoline supply. The EPA has set the level far higher than the market can absorb. That pushes refineries near bankruptcy and compels them to plead for exemptions, which anger the ethanol lobby.

The EPA proposes to make refiners take the hit for the exempted backlog of recent years in addition to the excessive mandates for 2026-27. That means higher prices, damage to car engines, and fewer good blue-collar jobs.

The RFS is a relic of the 1970s oil shocks. President Jimmy Carter warned of “catastrophe” and lavished subsidies on “gasohol.” Oil scarcity proved fleeting, but corn-state interests had discovered an entitlement, and in 2005 Congress discovered a new rationale: climate change. Congress set aggressive RFS targets, rising to 15 billion gallons of ethanol as U.S. gasoline consumption was projected to reach 150 billion gallons. The idea was to mandate as much as car engines could safely absorb: an ethanol content of about 10%. Thus E10 was born.

…..

The ethanol mandate is a deeply flawed policy. It does more harm than good for the environment, with an area the size of Michigan devoted to corn ethanol instead of something beneficial like natural habitat or food production—raising the prices of fuel and food as a result. If Congress could put the national interest above powerful special interests, it would repeal the RFS. That is unlikely to happen anytime soon, but there is an alternative.

In this new, short paper, Elaine Sternberg nicely explains the virtues of spontaneous orders. Here’s the summary:

Spontaneous order is crucial for understanding fundamental human institutions (e.g., language and the law, morals, markets and money) and for defending individual liberty. But its operation is often overlooked.

Spontaneous orders are self-generating, self-adjusting complex adaptive systems. They exist when a pattern that has not been arranged by any coordinator emerges from the interactions of multiple, dispersed individual elements.

Characterised by Adam Smith as the ‘invisible hand’ and by Ferguson and Hayek as ‘the result of human action, but not of human design’, spontaneous order in human institutions is perhaps more clearly understood as the ‘unintended coordination of intentional action’.

Spontaneous orders can integrate knowledge that is dispersed, dynamic, tacit and privileged. They can thus handle great complexity and arguably do so better than deliberately constructed orders.

Spontaneous orders respect individual liberty: they are essentially non-coercive, prove that order does not require law, and only function properly if their component elements can freely react to changing circumstances.

The power and pervasiveness of spontaneous orders show that government action, far from being essential, is seldom necessary and is often positively counterproductive. Spontaneous order justifies challenging regulation proposed for correcting market failure, promoting efficiency, or dealing with complex problems, including climate change, public health and welfare, and economic growth.

Empirical studies have confirmed that spontaneous order has been better than coercive regulation at generating economic growth, managing natural resources and providing key public services, and better than imposed rules at detecting fraud and disease.

[DBx: Where Prof. Sternberg writes that “order does not require law,” she really means that order does not require legislation.]

Mike Munger beautifully sings the transaction-costs-reducing achievements of Uber and AirBnB. A slice:

The bright-line distinction between producer and consumer, a relic of the Industrial Revolution, dissolves in platform space. This has consequences for policy, taxation, labor regulation, and even our intuitions about property. When excess capacity is commodified, ownership becomes less a categorical state and more a bundle of transferable rights that can be partitioned and sold temporarily.

In this sense, the “sharing economy” is poorly named. Nothing is being shared in the gift-exchange sense. What is being shared is temporary access. What is being commodified is excess capacity. Fifty years from now, observers will look back on our era with incredulity. Why did people buy all their own tools? Why did cities devote up to 30 percent of their usable road area to storing empty cars? (In Manhattan, it’s more than 40 percent!) Why did we allow trillions of dollars of capital to sit idle for 95+ percent of its lifespan?

The answer we will give — “Well, transaction costs were too high!”— will seem quaint.

Platforms are revealing that much of what we think of as “ownership” is really just expensive access insurance. Once platforms reliably provide that insurance, the original rationale for owning evaporates.

Arnold Kling instructively comments – here and here – on Alan Macfarlane’s great 1978 book, The Origins of English Individualism.

Scott Winship continues to explain that the U.S. economy “is not stagnant.” Two slices:

However, these perceptions of long-run decline are at odds with the facts. Certainly, Americans’ consternation about higher grocery bills and gas prices is valid, as are mounting concerns about housing costs, but it doesn’t paint a full picture of how financial circumstances have changed in just a couple of generations. Earnings trends over the past 50 years show that not only are middle-class earnings up significantly — by $23,000 among men working year-round and $34,000 among women — earnings growth among young men has been stronger during the past 35 years than in the previous 15. These findings belie many popular accounts of what ails the economy today.

…..

Social media is rife with unsourced charts depicting stagnant wages and internet memes lamenting the insecurity of “late-stage capitalism.” These posts are as likely to be shared by Tucker Carlson acolytes as by followers of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. But the best evidence on earnings trends presents two insurmountable problems for populists who blame supposedly stagnant living standards on economic developments and policy choices over recent decades.

First, nothing about the overall 50-year earnings trends for men or women indicates people had it better in the early 1970s. Earnings are essentially at all-time highs for both. And second, while the worst earnings trend over the past 50 years was for young men, the period that makes this long-term trend look unusually bad ended before the “China Shock” occurred, before immigration’s rapid acceleration in the 1990s, before the Great Financial Crisis, and before income concentration in the hands of “the top one percent” approached its peak.

The most powerful factions on the left and right today — both sides of the populist coin — start with the belief that we are in stagnation or decline, blame the usual targets, pronounce their favored policies, and then search for statistics to make their case. But for anyone who cares about workers rather than expanding their audience, that approach is counterproductive. The way to stronger earnings growth is to start by assembling the best statistics on the merits, assess their implications, determine the factors influencing them, and then craft policies consistent with those explanations. The typical worker is tens of thousands of dollars better off than in the past. We can and should do better, but it will do us no good to act as if we have made no progress.

David Henderson is thankful for freedom and the economic growth that it alone makes possible. A slice:

Maybe you’re skeptical of the idea that the CPI overstates inflation. Fine. Then do what economists Michael Cox and journalist Richard Alm did in their 1999 book, Myths of Rich & Poor: look at actual households’ consumption of goods and services. Cox and Alm showed that between 1970 and the mid-1990s, the average size of a new home increased from 1,500 square feet to 2,150 square feet, an increase of over 43 percent. They also looked at what was in and around the home. In 1970, only 34 percent of American homes had central heat and air conditioning; by the mid-1990s that had more than doubled to 81 percent. In 1970, 62.1 percent of all homes had clothes washers; by the mid-1990s, 83.2 percent had them. In 1970, only 29.3 percent of households had two or more vehicles; by the mid-1990s, that was up to 61.9 percent. That last statistic is even more impressive when you consider that over the same quarter century, the number of people per household fell from 3.14 to 2.64.

Cox and Alm even showed that by 1994 poor families did better on virtually every household item, from washing machines to color TVs to clothes dryers, than they had done in 1984. More impressively, what poor families had in their homes in 1994 was comparable to what the average family had in 1971.

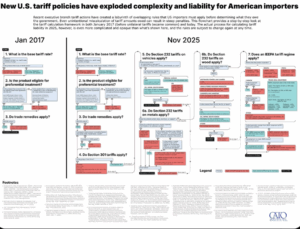

Scott Lincicome tweets this telling diagram: