Writing in today’s Wall Street Journal, former Senator Phil Gramm (R-TX) defends Ronald Reagan from the charge, popular today among protectionists, that the voluntary export agreement (launched during Reagan’s presidency) on Japanese automobiles is evidence that Reagan was a protectionist. Four slices:

During a debate that I participated in at the Harvard Club of New York in December, Oren Cass, founder of the think tank American Compass, tried to draft President Ronald Reagan into the ranks of trade protectionists. Mr. Cass quoted a claim that Reagan was “the greatest protectionist since Herbert Hoover” and said that he “took repeated aggressive protectionist trade actions against the Japanese in particular.”

Mr. Cass’s argument, now a standard protectionist claim, was that because Reagan in 1981 agreed to a temporary voluntary restraint deal limiting the number of Japanese automobiles that could be imported into the U.S., he was a protectionist. I pointed out to Mr. Cass that I saw Reagan “at least once a week” during that period while I was working on the president’s budget, which I co-authored in the House, and could attest that the president hated the deal. He agreed to the compromise only to prevent lawmakers from passing more extreme protectionist legislation.

…..

President Reagan’s support for free trade wasn’t based on any of the economic arguments that have dominated informed opinion on trade policy for 250 years. To Reagan, free trade was simply an economic extension of freedom. In his view, except in limited circumstances involving national security, government had no right to tell people that they had to buy a product so that someone else could benefit from producing it. In a 1988 radio address, he said that “open trade policy . . . allows the American people to freely exchange goods and services with free people around the world.”

…..

Protectionists argue the restraint agreement brought foreign auto investment to America, but Volkswagen—which wasn’t under the auto agreement—built its first U.S. plant in Pennsylvania in 1978. Foreign investment in U.S. auto plants between 1981 and 1994, when the restraint agreement was in force, averaged only $671 million a year in 2017 dollars but averaged $6.6 billion between 1995 and 2008 after the voluntary restraint ended.

It wasn’t protectionism but lower taxes, a more favorable regulatory climate and right-to-work policies that brought foreign auto investment to the U.S. and created a vibrant auto industry in the American South. Alabama, which didn’t produce a single automobile when the restraint ended, is now the fifth-largest auto-producing state due to foreign investments by Mercedes-Benz, Hyundai, Toyota and Honda.

…..

Reagan warned America to reject “the siren song of protectionism” and instead to embrace peaceful trading partners. “We should beware of the demagogues who are ready to declare a trade war against our friends . . . all while cynically waving the American flag,” he said. “The expansion of the international economy is not a foreign invasion; it is an American triumph, one we worked hard to achieve.” Americans would do well to remember his words.

My intrepid Mercatus Center colleague, Veronique de Rugy, decries the damage that Trump’s protectionism is inflicting on U.S. automakers. A slice:

These tariffs were supposed to protect American jobs and strengthen domestic manufacturing. Instead, they’re shrinking margins, reducing profits — and hence investment — and setting the stage for higher consumer prices.

If the goal is to strengthen American manufacturing, this probably isn’t the way. Douglas Holtz-Eakin reminds us how tariffs have repeatedly failed to save the steel industry.

GMU Econ alum Dominic Pino both rightly applauds the recent change in the tax code that allows permanent full expensing, and rightly criticizes the administration’s economically harmful protectionism. A slice:

Computer code isn’t unloaded from ocean vessels. No customs agent ever has to collect a tariff on an app before it appears in an app store. High tariffs provide yet another advantage to technology companies relative to manufacturing companies in government policy.

As Greg Ip of the Wall Street Journal pointed out, this is actually one of the reasons why the stock market hasn’t been affected as much since the initial shock of the April tariff announcement. Fifty years ago, a terrible GM earnings report like the one we just saw would have done a number on the stock market. Today, GM only has a market cap of $50 billion. The biggest tech companies are over $1 trillion. The “old economy” that is hurt more by the tariffs simply doesn’t factor as much into overall stock market performance as the “new economy.”

Punishing the “old economy” is not what populists want, but if you want to continue to have an economy that structurally favors technology companies, tariffs are a great way to do that.

Also from Dominic Pino is this warning: “General Motors will be nationalized at some point, and you’ll be expected to feel patriotic about it.” A slice:

Politicians simply can’t allow GM to go under, even though it deserved to in 2009, and its financial situation will probably merit it again in the future. Between their mismanagement and a torrent of government regulations — safety rules, green rules, and trade rules — it’s going to eventually become impossible to keep going. In some sense, it’s an arm of the government already, meekly complying with every new mandate under the knowledge that it only continues to exist because of the bailout.

It’s possible for a company to reinvent itself, and many have. Barnes & Noble, for example, is actually doing quite well despite competition from Amazon. It realized it needed to change and executed a strategy to do that. GM has not demonstrated that kind of leadership or innovation. And it can’t because it is locked into onerous union contracts.

The only way GM doesn’t get nationalized is if it hangs on long enough that all the old politicians and voters who are nostalgic for the heyday of the company die first. But either Trump or Biden would nationalize GM in an instant if that’s what was necessary to save the company. And they’d act like they were doing you a favor by spending your tax dollars to prop up a zombie firm that the government played a part in killing.

The Editorial Board of the Wall Street Journal identifies “the price of winning the trade war.” Two slices:

The trade deal President Trump announced with Japan Tuesday evening is good news—in the narrow sense that it defuses what could have been an extended tariff war with America’s most important ally in Asia. But if this is winning a trade war, we’d hate to see what losing looks like.

Mr. Trump hailed the pact with characteristic modesty as “perhaps the largest Deal ever made.” Details remain sparse, but the core appears to be a Japanese commitment to invest $550 billion in the U.S. while reducing barriers to imports of American agricultural products such as rice. In exchange, Mr. Trump will reduce his “reciprocal” tariffs on Japan to 15% from 25%—including, apparently, on autos.

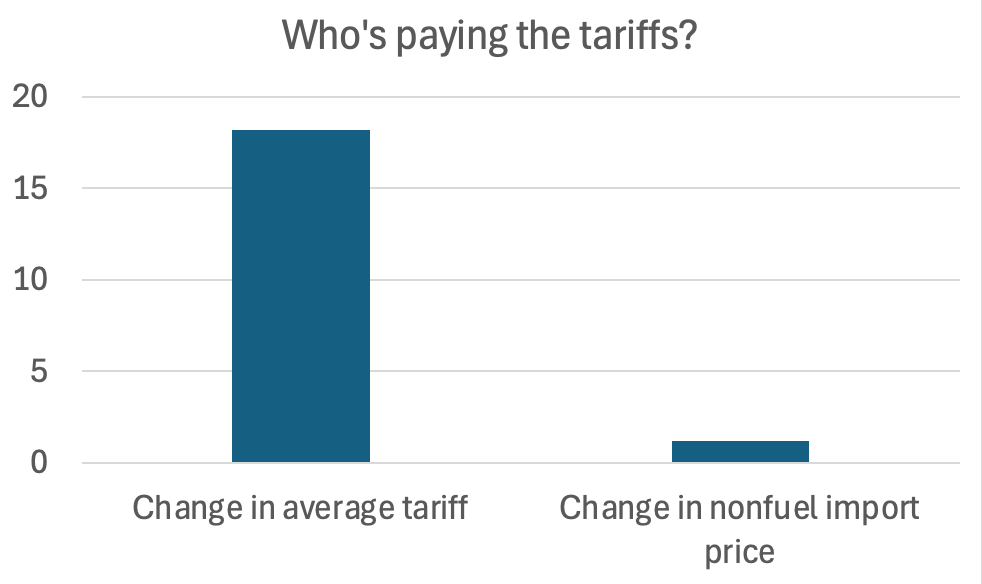

The new tariff rate is good news only as relief from 25%. This is still a 15% tax increase on imports from Japan. And don’t believe the White House spin that Japanese exporters will pay this tax. They might absorb some of it, depending on the product and the competition. But American businesses and consumers will pay more too and thus be either less competitive or have a lower standard of living.

That $550 billion in new Japanese investment also sounds better than it may be once we know the details. Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba suggested Tokyo will offer government loans and guarantees to support these “investments,” with the aim “to build resilient supply chains in key sectors.”

This raises the prospect that this money, if it arrives, will be tied up in Japanese industrial policy. And American industrial policy, since Mr. Trump said Japan will make these investments “at my direction” and the U.S. “will receive 90% of the Profits.” Yikes.

By the way, more investment inflows by definition mean a larger trade deficit in the U.S. balance of payments. Has someone told the President about this?

The U.S. could have had more Japanese investment all along, except Mr. Trump helped chase it away. The current President and President Biden did their best to thwart a $14.9 billion acquisition of U.S. Steel by Nippon Steel ahead of last year’s election, before Mr. Trump acquiesced in June. Perhaps if Japanese companies were more confident they’d get a fair shake in the U.S., we wouldn’t need all these loan guarantees and trade deals to unlock capital commitments for American jobs.

…..

As for the claim that Mr. Trump is “winning” this trade war, that depends on how you define victory. It’s true Mr. Trump is showing he can bully much of the world into accepting higher tariffs. The size of the U.S. market is powerful negotiating leverage. The pleasant surprise so far is that most countries haven’t retaliated, which has spared the world from a 1930s-style downward trade spiral.

But Mr. Trump is showing the world that the U.S. can change access to its market on presidential whim. Countries will diversify their trading relationships accordingly, as they already are in new bilateral and multilateral deals that exclude the U.S. China will expand its commercial influence at the expense of the U.S. Beijing has also shown that two can play trade bully ball. It retaliated against Mr. Trump’s 145% tariffs with export restraints on vital minerals, and Mr. Trump agreed to a truce.

By the time this trade war ends, if it ever does, the average U.S. tariff rate may settle close to 15% from 2.4% in January. That’s an anti-growth tax increase.

Reason‘s Eric Boehm is correct: “Trump’s ‘deal’ with Japan is another loser for Americans.” A slice:

But, as with earlier “deals” struck with the United Kingdom and Vietnam, this agreement looks like a bad one for the United States. Not only does it raise taxes on American consumers, but it leaves American automakers at a distinct disadvantage relative to their Japanese competitors.

Under the terms outlined by Trump in a Truth Social post on Tuesday, imports from Japan will be subject to a 15 percent tariff when they enter the United States. Yes, that’s lower than the 25 percent tariff that the president has been threatening to impose on Japanese imports, but it is still a huge tax increase relative to existing tariffs on Japanese goods.

Previously, the average tariff rate on American imports of Japanese goods was less than 2 percent, according to the World Bank’s data. In other words, Trump’s “deal” amounts to roughly a 650 percent tax increase on those imports. Those taxes, like all tariffs, will be paid by Americans.

Peter Earle busts the myth – one repeated by Trump – that the United States has for years been “ripped off” by our trade arrangements with other countries. Two slices:

By any serious measure, and certainly by every economic metric, the claim that the United States has been “ripped off” or “mistreated” by its trading partners over the past several decades is incoherent. The rhetorical scaffolding upon which the Trump administration’s protectionist tariff regime rests is a fundamentally flawed understanding of international trade. It substitutes a mercantilist worldview — discredited since the eighteenth century — for evidence-based economic policy, and in so doing risks sabotaging the very system that has helped drive US prosperity, innovation, and leadership in global commerce.

The administration’s argument is built on the premise that large bilateral trade deficits — particularly with China, Mexico, Germany, and Japan — represent exploitation. In fact, a trade deficit is not a measure of being “taken advantage of;” it is a simple macroeconomic identity. It reflects the fact that the United States consistently imports more than it exports, with capital inflows from abroad financing both private investment and public debt. This inflow — recorded as a capital account surplus — signals that global investors view the US as a safe and attractive destination for capital. Far from being a symptom of decline, this pattern is a reflection of economic strength and international confidence in US institutions. Trade deficits are not inherently bad; in fact, they often correlate with periods of strong growth and low unemployment.

…..

Moreover, the assertion that past trade agreements — such as NAFTA, the WTO accession of China, or the US-Korea FTA — were one-sided giveaways is economically unserious. Those agreements were negotiated to promote mutual gains through the reduction of barriers to trade and investment. Some industries contracted, as expected in any process of specialization and reallocation. But far more jobs were created in sectors where the US holds competitive advantages: high-tech manufacturing, advanced services, and capital-intensive production. Consumers have benefited from lower prices, and American firms gained access to global supply chains that improve productivity and innovation.

John Stossel criticizes Tucker Carlson and some other American conservatives for their hostility to free markets.

There is yet another reason to beware the use of communitarian arguments in a political setting. Just as large political societies are not families writ large, so they are not communities writ large. A community requires more than people who live side by side or individuals who owe allegiance to a single sovereign. It requires that people within the community show some concern for each other. Equal concern and respect cannot be rammed down the throats of people who wish to direct their emotional energies elsewhere. What is required is some willing acceptance and recognition of the communities by their members. Communities can be destroyed from without, but they cannot be created from without; they must be built from within. Thus any effort to use state machinery to create a sense of community is likely to backfire and to displace voluntary groups that could otherwise be formed by free and independent people.

There is yet another reason to beware the use of communitarian arguments in a political setting. Just as large political societies are not families writ large, so they are not communities writ large. A community requires more than people who live side by side or individuals who owe allegiance to a single sovereign. It requires that people within the community show some concern for each other. Equal concern and respect cannot be rammed down the throats of people who wish to direct their emotional energies elsewhere. What is required is some willing acceptance and recognition of the communities by their members. Communities can be destroyed from without, but they cannot be created from without; they must be built from within. Thus any effort to use state machinery to create a sense of community is likely to backfire and to displace voluntary groups that could otherwise be formed by free and independent people. Once the rulers of a society – in a democracy, the citizenry – become hostile to decentralized, trial-and-error processes, legal institutions will change accordingly. The sclerosis [Joel] Mokyr fears comes not because dynamism destroys itself but because people abandon it, either because they do not understand what is at stake or because they do not care.

Once the rulers of a society – in a democracy, the citizenry – become hostile to decentralized, trial-and-error processes, legal institutions will change accordingly. The sclerosis [Joel] Mokyr fears comes not because dynamism destroys itself but because people abandon it, either because they do not understand what is at stake or because they do not care.