The following record of my stream-of-consciousness thoughts was inspired by the wedding-cake case being heard today by the United States Supreme Court and by a stimulating conversation that I had with some of my GMU Econ colleagues, especially Virgil Storr.

…….

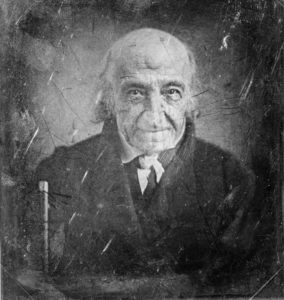

Jim Buchanan starts one of his papers (I don’t now recall which) by noting that an important distinction between markets and government is that exit is much easier in markets than it is in governments. The right to say “no” – “the right not to contract” (to steal a term that I once heard Randy Barnett use) – is indeed an essential part of markets.

Normally, this right to say, and the ease of saying, “no” – the right to exit and the ease of exiting – are normally thought of as protecting consumers. Because McDonald’s cannot force you to buy its hamburgers, it has an incentive to offer to you a good burger at a low price. But even if McDonald’s refuses to improve its burgers, it can’t harm you. Because you can easily choose to dine at any number of other restaurants, or at home, if you don’t like McDonald’s offerings, McDonald’s has no power over you no matter how many billions of dollars Ronald McDonald has stuffed into his McBank account.

But if buyers have – and should have – the right to say “no,” shouldn’t sellers have the same right? Shouldn’t there be symmetry? After all, those whom we conventionally classify as “sellers” are also – and in the same transactions – buyers. Sellers buy the money – sellers buy the purchasing power – of those whom we conventionally classify as “buyers.” Similarly, buyers also are sellers of the money – buyers also are sellers of the purchasing power – that is sought and bought by those whom we conventionally classify as “sellers.”

And so if the right and ability to say “no” is important for the functioning of markets, why is this right and ability not more widely understood as belonging to merchants, manufacturers, and other sellers no less than it belongs to people in their role as consumers?

If, say, Baker offers cakes that are judged by consumer Jones as being of poor quality, Jones is not damaged because Jones is not forced to buy Baker’s cakes. But suppose that, while Jones has the right to refuse to trade with Baker, Baker has no right to refuse to trade with Jones. Doesn’t Jones then have the power to inflict harm on Baker – harm that is analogous to the harm that Baker would inflict on Jones if Jones had no right to refuse to trade with Baker?

Asked differently: if we understand that Baker would be irresponsible and a source of harm to consumers if consumers could not refuse to trade with Baker, shouldn’t we understand also that consumers would become irresponsible and a source of harm to Baker if Baker could not refuse to trade with consumers? If the right and ability to say “no” is important to discipline market participants to serve each other’s best interest, shouldn’t this right and ability be possessed by Baker no less than it is possessed by Jones and other consumers?

Despite my firm conviction that the ultimate goal of economic activity is to promote consumption rather than to promote production, all of my priors prompt me to believe that the right to say “no” – the right not to contract – should be possessed equally by all market participants, on the selling as well as the buying side.

I understand that money is a far more homogenous good than is even the most commodified good or service sold by manufacturers or merchants. I understand also that the number of people who possess and are willing to spend money is much larger than is the number of people who possess and are willing to sell any of the other particular goods or services exchanged on markets. Is this reality sufficient to explain why many people believe that while no consumer should be forced to trade with, say, a baker, no baker should have the right to refuse to trade with a consumer?

Government prohibitions do always more mischief than had been calculated and it is not without much hesitation that a statesman should hazard to regulate the concerns of individuals as if he could do it better than themselves.

Government prohibitions do always more mischief than had been calculated and it is not without much hesitation that a statesman should hazard to regulate the concerns of individuals as if he could do it better than themselves. Take, for instance, the question of the effects of machinery. The opinion that finds most influential expression is that labor-saving invention, although it may sometimes cause temporary inconvenience or even hardship to a few, is ultimately beneficial to all. On the other hand, there is among working-men a wide-spread belief that labor-saving machinery is injurious to them, although, since the belief does not enlist those powerful special interests that are concerned in the advocacy of protection, it has not been wrought into an elaborate system and does not get anything like the same representation in the organs of public opinion.

Take, for instance, the question of the effects of machinery. The opinion that finds most influential expression is that labor-saving invention, although it may sometimes cause temporary inconvenience or even hardship to a few, is ultimately beneficial to all. On the other hand, there is among working-men a wide-spread belief that labor-saving machinery is injurious to them, although, since the belief does not enlist those powerful special interests that are concerned in the advocacy of protection, it has not been wrought into an elaborate system and does not get anything like the same representation in the organs of public opinion. To suggest, in the words of political scientist Chalmers Johnson that “the United States is in danger of ending the 20th century as the leading producer of ICBMs and soybeans, while the Japanese monopolize everything else” is tantamount to saying that the Japanese are so stupid that they will, through their exports, sell off practically everything they have without getting anything concrete in return just to achieve “monopolies,” a contradiction of immense proportions. How could a country smart enough to monopolize world markets be stupid enough never to demand payment in something real and tangible – not just in dollars, which are just so much paper (or blips on a bank’s computer tape) if they are never spent?

To suggest, in the words of political scientist Chalmers Johnson that “the United States is in danger of ending the 20th century as the leading producer of ICBMs and soybeans, while the Japanese monopolize everything else” is tantamount to saying that the Japanese are so stupid that they will, through their exports, sell off practically everything they have without getting anything concrete in return just to achieve “monopolies,” a contradiction of immense proportions. How could a country smart enough to monopolize world markets be stupid enough never to demand payment in something real and tangible – not just in dollars, which are just so much paper (or blips on a bank’s computer tape) if they are never spent? It is not at all to the point to say, as [Werner] Sombart and the Germans regularly do, that no one could be so stupid as not to know the difference between money and wealth, that the ancient fable of Midas is enough to dispel this illusion from any mind. Certainly the mercantilists did not identify the two explicitly (though they came close enough to that at many points), but it is just as unquestionable that only on the basis of such a premise can any sort of sense be made out of the great bulk of mercantilistic utterances or policies. And why should it be otherwise? Conditions are no different today in most of the civilized capitalistic world. The man from Mars reading the typical pronouncement of our best financial writers or statesmen could hardly avoid the conclusion that a nation’s prosperity depends upon getting rid of the greatest possible amount of goods and avoiding the receipt of anything tangible in payment for them.

It is not at all to the point to say, as [Werner] Sombart and the Germans regularly do, that no one could be so stupid as not to know the difference between money and wealth, that the ancient fable of Midas is enough to dispel this illusion from any mind. Certainly the mercantilists did not identify the two explicitly (though they came close enough to that at many points), but it is just as unquestionable that only on the basis of such a premise can any sort of sense be made out of the great bulk of mercantilistic utterances or policies. And why should it be otherwise? Conditions are no different today in most of the civilized capitalistic world. The man from Mars reading the typical pronouncement of our best financial writers or statesmen could hardly avoid the conclusion that a nation’s prosperity depends upon getting rid of the greatest possible amount of goods and avoiding the receipt of anything tangible in payment for them.