My tv yesterday afternoon was tuned to a local news telecast by DC’s NBC 4. I wasn’t paying close attention to the telecast, but I did catch part of a report about how Trump allegedly gave a misleading account of what his administration did to secure the purchase of aircraft from Boeing rather than from some foreign manufacturer. The report featured a ‘fact checker’ who disputed some aspect of Trump’s claim. Because I wasn’t paying close attention, I never got the details. (I looked this morning on NBC 4’s website for the report, but couldn’t find the report.)

But these details here aren’t important. I write here to comment on a clip of Trump that was played during this report. In this clip, Trump boasts that, because of his administration’s actions, the aircraft buyers “bought it from us” (or “bought them from us”). The part that caught my full attention is the “from us.”

Such language is common. If a non-American buys, say, building products from Georgia-Pacific or jetliners from Boeing, Americans often say – as Trump said here – that they “bought it from us” (or that “we sold it to them”). Yet although common, such language is highly misleading.

Who is the “us”? If a non-American bought a jetliner from Boeing, that foreigner didn’t buy that jetliner from me. I neither own stock in Boeing nor work for Boeing. This sale by Boeing is not a sale by me; the purchase made by Boeing’s customer is not a purchase from me. The fact that my passport is issued by the same agency (i.e., the U.S. government) that issues the passports of most of Boeing’s owners and workers does not, contrary to the widespread presumption, make me one with Boeing or otherwise render the use of the first person plural pronoun “us” appropriate in this case. Using the word “us” in this way – here to refer to all Americans – gives the wholly mistaken impression that all Americans benefit whenever Boeing (or any other American company) makes a sale to non-Americans.

Here’s just one of countless specific ways to see why this use of “us” is misleading. Assume that in the actual case of these aircraft being bought from Boeing that Boeing’s owners and workers spend none of their profits and higher wages on sending their children to George Mason University. Further assume that if non-Americans had instead bought the aircraft from Airbus that some of Airbus’s owners or workers would have spent some of their resulting profits and higher wages on sending their kids to George Mason University to study economics. These assumptions are not implausible.

In this alternative scenario, because I am employed to teach economics at George Mason University, I would have benefitted had the non-American bought the aircraft, not from Boeing, but instead from Airbus.

Don’t get hung up on my hypothetical alternative scenario. Whether or not this scenario itself would be accurate in its details is unimportant. What is important is the recognition that

(1) the fortunes or misfortunes of any particular producer or producers within your country are not the same as your fortunes or misfortunes (here, if you own no Boeing stock, Boeing’s higher profits are not your higher profits), and, relatedly,

(2) ‘seeing’ the full consequences of international trade requires an examination not only of the immediate set of actual transactions (here, non-Americans’ purchase of aircraft from Boeing) but also of (a) transactions subsequent to the immediate ones, and (b) transactions that didn’t happen as a result of the transactions that did happen.

The use of “us” in cases such as this reflects the mercantilist notion that each country is a large firm competing for sales against other countries. Such a notion is central to Trump’s understanding of trade; it is a wholly mistaken notion.

I admire the ease with which in certain countries it is possible to perpetuate the most unpopular things by giving them a different name.

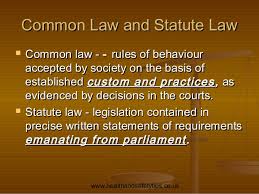

My conclusion is that so far as Private Law – the law which governs our conduct in our ordinary transactions with each other – is concerned, the influence of legislation – of written law – has been exceedingly small.

My conclusion is that so far as Private Law – the law which governs our conduct in our ordinary transactions with each other – is concerned, the influence of legislation – of written law – has been exceedingly small. [K]illing the goose that lays the golden egg is a viable strategy from a purely political standpoint, provided the goose does not die before the next election.

[K]illing the goose that lays the golden egg is a viable strategy from a purely political standpoint, provided the goose does not die before the next election. For most of US history, however, there has not been a single, unified “capital” or “labor” interest regarding trade policy, because there are many different types of capital and labor that are affected by trade in different ways. Capital owners and workers employed in industries that compete against imports (iron and steel, textiles and apparel) typically have a much different view of trade policy than the capital owners and workers employed in industries that export (agriculture, machinery, or aerospace).

For most of US history, however, there has not been a single, unified “capital” or “labor” interest regarding trade policy, because there are many different types of capital and labor that are affected by trade in different ways. Capital owners and workers employed in industries that compete against imports (iron and steel, textiles and apparel) typically have a much different view of trade policy than the capital owners and workers employed in industries that export (agriculture, machinery, or aerospace). Had the Pilgrims continued communal farming, this Thursday might be known as “Starvation Day” instead of Thanksgiving.

Had the Pilgrims continued communal farming, this Thursday might be known as “Starvation Day” instead of Thanksgiving. An early Christmas gift arrived today: my long-awaited copy of Doug Irwin’s new book,

An early Christmas gift arrived today: my long-awaited copy of Doug Irwin’s new book,