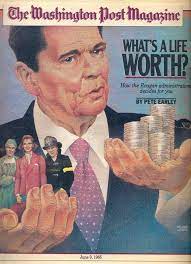

This morning in San Antonio, at a Law & Economics Center seminar, Caroline Cecot – a GMU colleague of mine over in the Scalia School of Law – gave a great talk on risk assessment and risk management. In one of her PowerPoint slides, Caroline showed the June 9th, 1985, cover of The Washington Post Magazine (shown here).

This morning in San Antonio, at a Law & Economics Center seminar, Caroline Cecot – a GMU colleague of mine over in the Scalia School of Law – gave a great talk on risk assessment and risk management. In one of her PowerPoint slides, Caroline showed the June 9th, 1985, cover of The Washington Post Magazine (shown here).

Seeing this slide brought back memories. I happened to be in northern Virginia on June 9th, 1985. Still living in Auburn, Alabama, I was then visiting Fairfax looking for an apartment, for I – along with my friend George Selgin – were to begin our academic careers that Fall semester as members of George Mason’s Economics faculty. I well recall then encountering that issue of the magazine and disliking its cover and liking no less the accompanying article by Pete Earley.

As I explain below, had the artist truly wished to portray cost-benefit analysis accurately, he or she would have portrayed Reagan holding in his left hand, not money, but flesh-and-blood people – just as in his right hand he holds flesh-and-blood people. Both hands would have held people; none would have held money.

Earley began his article with an account of a 1978 industrial accident in Willow Island, West Virginia. That tragedy took the lives of 51 workers. Earley then discussed the Reagan administration’s fondness for cost-benefit analysis and its acceptance of the notion that monetary values should be attached to human life as a means of determining if regulatory steps to reduce risks of death are or are not cost-effective. Earley closed his article in this way:

How much is a construction worker’s life worth? The question could only be asked in Washington.

In Willow Island death wears a face.

This final line is powerful. It’s also true. But its truth does not point to the conclusion that Earley, or most people, suppose.

Industrial accidents are visible. They are events of concentrated terribleness. They can be photographed and filmed. The names of the victims are known and reported. Pictures of them when they were alive – and of the parents, spouses, and children who survive to mourn – are shown. Faces. No one this side of sociopathy can avoid experiencing genuine sympathy for the dead and their surviving loved ones.

But this emotional reaction only raises the importance of doing our best to use credible cost-benefit analyses to guide government regulation of safety. The reason is that using more resources to reduce, say, construction-workers’ risks of being killed or injured while on the job is to have fewer resources used to satisfy other human wants, including reducing risks of death and injury in other settings.

What President Reagan should have been portrayed as weighing is not people and money, but people and people. Money is only a medium of exchange and a measure of economic value. The goal of some action, private or public, might be expressed as “saving money.” But of course no one takes that action in order to accumulate money for the sake of accumulating money. The money that’s ‘saved’ by taking that action will be used to procure some real goods or services of value to real human beings.

Some of these real goods and services will, and some will not, increase health and safety. Either way, the calculus isn’t “people vs. money.” (If this choice were the one at hand, only a monster would choose money.) The calculus is “human wants A, B, and C” vs. “human wants X, Y, and Z.” That these wants can usefully be expressed in monetary terms is true. But if such expression were to have occurred on that Washington Post Magazine cover, then Reagan should have been depicted as holding money, and only money, in both hands.