If there’s one positive thing to be said about President Donald Trump’s latest tariff announcement, perhaps it is this: Few trade policy moves are more abundantly counterproductive and costly than tariffs on cars and car parts.

That’s a lesson the Trump administration is apparently determined to learn the hard way. On Wednesday, Trump announced a new set of 25 percent tariffs that will apply to imported cars and the components that go into cars built in the United States. Trump says those moves will promote domestic auto manufacturing, but that seems unlikely. Instead, the tariffs will make cars and light trucks more expensive, and will likely reduce the number of cars made and sold in America. They are bad news for auto workers, auto dealers, and consumers.

…..

In the wake of Wednesday’s announcement, Jonathan Smoke, a chief economist at Cox Automotive told The New York Times that 25 percent tariffs on cars and car parts would add an estimated $3,000 to the cost of cars built in the United States, with higher price hikes likely for foreign-made cars. He estimated that American factories will produce about 30 percent fewer cars as a result of the tariffs and that the industry is prepared for “disruption to virtually all North American vehicle production.”

But why would even American-made cars be impacted by the tariffs? Because there really is no such thing as a fully American-made car. According to an annual survey published by American University, there was not a single car brand that sourced all its parts domestically in 2024. New tariffs on car parts will hurt some brands more than others—Tesla, notably, seems poised to be hurt less than most of its competitors—but the damage will be widespread.

…..

Three decades after the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed, the supply chains for American automakers stretch across the whole continent. “Ultimately, a vehicle is considered an import when it is shipped to the United States after undergoing final assembly in another country. But many vehicles—including those assembled in America—are composites of parts that come from all over the world,” notes The New York Times in an explainer about the modern automotive manufacturing supply chains that someone at the White House probably ought to read.

Drawing these political distinctions between domestic and foreign cars is pretty silly in a marketplace that is increasingly integrated. Is a BMW built in South Carolina a foreign car because of the name on the hood? What about a Toyota truck assembled in Tennessee? What about a Ford that’s built in Mexico with parts sourced from every corner of the globe? None of these questions are as black-and-white as the Trump administration wants to make them, and that’s just fine—we should trust the market, not politicians, to build the best car.

In the Wall Street Journal, Jared Bernstein and Dean Baker have a piece about how the Trump administration’s sweeping agenda of protective tariffs, meant to restrict imports to create a manufacturing renaissance, will fail. These authors propose instead a sprawling array of subsidies, tax credits, and federal grants aimed at coaxing domestic production in “strategic” industries. These are the two dominant industrial-policy frameworks today — and they are both deeply flawed.

…..

Further, the fantasy of full-scale reindustrialization of the workforce is just that. Let’s even imagine that higher import taxes on manufacturers and producers — making the inputs they use more expensive — will convince most of them that investing in the U.S. is a good deal, leading to more manufacturing on our shores. Even in this unlikely scenario, there will be no boom in manufacturing jobs. That’s because the drive to be efficient — the competitive pressure to produce more and better at lower costs — will require more automation.

The alternative is one that the proponents of industrial policy for the sake of job creation in manufacturing haven’t considered. If manufacturing were to re-employ a large number of workers, it would mean that they must diminish their automation and, in doing so, lower their productivity. And lower productivity means lower real wages.

Yet those who clamor for reindustrialization (whatever that means, considering that industrial output and capacity today are at all-time highs and manufacturing output is 177 percent higher than the last time the U.S. ran a trade surplus in 1975) naively suppose that government-engineered increases in manufacturing employment will, by some miracle, not reduce manufacturing wages. America specializes in high-value production. That’s what happens when you are a rich country: Your workers are highly productive and have good employment options, so their wages rise. The closer we’ll get to restoring the American economy of the 1950s the closer we’ll get to reducing Americans’ real wages — and to worsening Americans’ work conditions — to what these were 70 years ago.

…..

Ultimately, tariffs and subsidies are two sides of the same costly coin. Both cases rely on the idea that politicians and bureaucrats are better at allocating resources than the market. Both underestimate the dynamism and adaptability of private enterprise. And both overpromise: tariffs will not bring back 1950s-style manufacturing employment, and subsidies will not create a resilient, self-sustaining industrial base or the “industries of the future.”

If the goal is genuine economic strength, we should stop trying to micromanage the economy through protectionism or top-down industrial policy. Instead, we should focus on creating the conditions for broad-based growth: a stable fiscal environment, low barriers to entrepreneurship, and a regulatory framework that encourages investment rather than punishing it. Oh, and also a commitment to a policy of free trade.

Industrial policy, whether dressed up as tariffs or as handouts, distracts from these fundamentals. And in doing so, it undermines the very prosperity it claims to build.

So much for the idea that President Trump views tariffs as a negotiating tool to reduce everyone else’s tariffs. That was always implausible, and the illusion went poof Wednesday with Mr. Trump’s executive order imposing 25% tariffs on all imported cars and trucks. He wants border taxes for their own sake, so get used to it.

“We’re going to charge countries for doing business in our country and taking our jobs, taking our wealth,” the President said in unveiling the tariffs. It’s pointless trying to persuade him that nobody is stealing Americans’ lunch and that trade can be good for both parties. But readers should know they are about to pay more for their cars and have less choice to boot.

Mr. Trump justifies his car tariffs as a “national security” threat under Section 232 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act. As we wrote in 2019 when he tried this gambit, he apparently fears the attack of the killer Toyotas.

Canada and Mexico, those global menaces, account for about half of U.S. auto imports. U.S. allies in South Korea, Japan and Europe account for almost all the rest. Imports give Americans more choices, and at lower prices, than they would otherwise have if all cars sold in the U.S. had to be made domestically. Americans as a result can afford more and better cars than they could a few decades ago. This is a security threat to whom exactly?

…..

Car makers have already invested countless billions in efficient supply chains to make cars that middle-class Americans can afford. They will now have to spend hundreds of billions more that could be invested in more productive ways. And all because Mr. Trump has an economic development model based on the fantasy of “import substitution.” That model kept India poor for decades.

President Biden sought to transform the U.S. economy based on his vision of government industrial policy. Mr. Trump is also trying to transform the economy according to his industrial vision.

GMU Econ alum Dominic Pino describes Trump’s “Fact Sheet” on tariffs as Bidenesque. Three slices:

It would be nice if economically illiterate White House “fact sheets,” a regular occurrence under the Biden administration, were a thing of the past. But Trump’s fact sheet justifying auto tariffs is positively Bidenesque.

Like Biden, Trump is abusing economic powers of the president intended for national defense to do something he wants to do regardless of any defense concerns. Biden used the Defense Production Act to support green energy, and now Trump is using Section 232 national-security tariffs to protect the car industry.

…..

Trump thinks it’s worth it to abuse the process in this way because, as the fact sheet says, “Studies have repeatedly shown that tariffs can be an effective tool for reducing or eliminating threats to impair U.S. national security and achieving economic and strategic objectives.”

What studies? Let’s go through them one by one:

- “A 2024 study on the effects of President Trump’s tariffs in his first term found that they ‘strengthened the U.S. economy’ and ‘led to significant reshoring’ in industries like manufacturing and steel production.”

- This is not a study, but rather an article on the website of the Coalition for a Prosperous America (CPA), a lobbying group that supports tariffs. To back up the claim of “significant reshoring,” the author lists three instances of companies creating a total of 1,345 jobs after the China tariffs and claims that the steel tariffs created 4,000 jobs. Granting for sake of argument that these numbers are correct, 5,345 jobs is hardly “significant,” accounting for 0.0033 percent of the roughly 163 million employed Americans. Other evidence provided is that the steel tariffs benefited steel companies, which . . . of course they did. Nowhere does the author consider the jobs lost due to higher input costs for manufacturers; in fact, he specifically rejects such analysis and says tariffs should only be “judged based on the targeted industries.” Of course tariffs can benefit the targeted industry, but the existence of concentrated benefits does not justify dispersed costs.

…..

This is the Biden economics playbook: Abuse national-security laws to do something you want to do anyway, purposefully ignore actual economic research on the topic, find other “research” from “experts” you like, and — bizarrely, coming from Trump — cite the Economic Policy Institute and Janet Yellen to support you.

Scott Sumner ponders “the new China Shock.” Two slices:

There’s a widespread perception that trade with China caused increased unemployment in America. This is false. Imports from China did reduce jobs in some industries, but this did not have any effect on the overall unemployment rate, as even more jobs were generated in other industries.

Last year, the Chinese trade surplus rose to nearly a trillion dollars. If the mercantilists were correct, then China should be experiencing a boom in manufacturing employment. In fact, just the opposite is occurring—millions of manufacturing jobs are being lost and China’s unemployment rate is higher than ours.

…..

Automation was also the primary cause of job loss in US manufacturing. Unfortunately, politicians have blamed the job loss on trade, and this has contributed to the global rise in nationalism. If trade really were the issue, then China’s vast trade surplus would be generating lots on manufacturing jobs. Instead, they’ve lost over 7 million such jobs, just since 2011

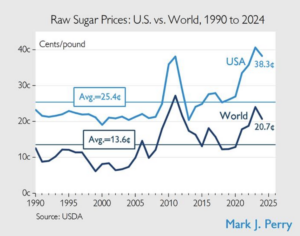

Fabian Wintersberger sensibly calls for an end to sugar tariffs and corn subsidies.

Speaking of sugar protectionism in the U.S., GMU Econ alum Mark Perry shares these data: