Trump again defensively lashed out at a private business person who dares to predict that American consumers will suffer higher prices as a result of Trump’s tariffs.

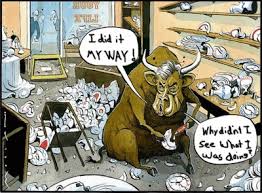

Forget the childishness of Trump’s behavior. Overlook his cowardly refusal to take responsibility for whatever ill-consequences his policies inflict. Ignore the inconsistency of Trump’s actual actions with the boastful claims of his supporters that he tells it like it is. Disregard the unseemliness of the president of the United States behaving like a sixth-grade schoolyard bully.

Instead, recognize the inescapable reality that someone must pay the cost of Trump’s tariffs, and there are only three groups who are candidates to foot this bill (or to share in footing this bill): American consumers, American businesses, and foreign producers.

Trump angrily denies that his tariffs will raise prices for American consumers (except, perhaps, for parents who purchase dolls for their children). So that leaves American businesses and foreign producers.

Let’s assume for the moment that the entire burden of the tariffs is absorbed by American businesses. The result, of course, is a tax on the operation of these American enterprises. And because Trump’s tariffs, even just the baseline ones, are steep, this tax is heavy. The return on investment in the businesses that are absorbing his tariffs falls. Over time, these businesses will shrink as will employment in these businesses.

You’ll not charge me with venturing out on a limb to suppose that Trump would deny that his tariffs are a burdensome tax on many American businesses.

So that leaves foreign producers (or foreign merchants). Trump wants the American people to believe that the full brunt of his tariffs is borne by these foreigners. If the tariffs do not raise prices paid by American consumers, and do not cause American importers and American producers who use imported inputs to incur any tariff-related costs, it must be the case that the foreigners who export to America lower the prices of their exports by the full amount of the tariffs and do not reduce the quantities or the quality of the outputs that they export to the United States. (If foreigners reduce the quantities that they export to U.S., prices paid by Americans would rise even if foreigners lower the prices they charge by the full amount of the tariffs. The reason is that prices rise when supplies fall.)

This latter scenario is wildly unrealistic (and, unsurprisingly, inconsistent with the empirical record). Yet it is presumably the scenario that the president of the United States wants the American people to believe will prevail.

So let’s humor the president of the United States and grant that this widely unrealistic scenario will prevail – namely, again, that foreign producers and exporters will lower the prices they charge Americans for their exports by the full amount of Trump’s tariffs and not reduce the quantity or quality of what they export to the U.S.

What, then, becomes of Trump’s boast that his tariffs will spur increased manufacturing in the U.S.? What is the fate of his avowal that his tariffs will prevent us Americans from being dependent on foreigners for critical supplies?

That boast and avowal necessarily become empty. If tariffs don’t cause prices in the U.S. to rise – to rise either directly as tariffs are passed through as higher prices to American buyers, or to rise indirectly as American importers, and American firms that use imports as inputs, cut back on their sales and production – then American producers whose outputs compete with imports will confront the same amount of competition from imports that they confronted before the tariffs were raised.

With the post-tariff prices of imports unchanged, American buyers will have no incentive to shift their purchases from imports to domestically produced substitute goods. The American producers who are meant to be ‘protected’ by the tariffs will enjoy no protection whatsoever. Demand for their outputs will not rise and, thus, they’ll not increase their production. In turn, they’ll not employ more workers.

……

Anyone who swallows all that Trump says about his tariffs is gullible. Such a person is someone who allows Trump to trap him or her into a logical impossibility. Either Trump himself is so astonishingly stupid as to not grasp the illogic of his claims, or – what is much more likely – Trump has no respect for his base. He treats the people in his base with contempt; he plays them as if they are stupid.

This outcome cannot be escaped by the cheap tack of pointing to Trump’s creds as a businessman or by the juvenile fun to be had by calling me (or any other economist) a pointy-headed, cosmopolitan, coddled, tenured, out-of-touch, ideologically benighted elite who doesn’t know what time it is. This outcome is a matter of ironclad logic: Either Trump’s tariffs do protect some American producers from foreign competition (in which case the tariffs must result in higher prices paid by Americans) or the tariffs don’t result in Americans paying higher prices (in which case the tariffs cannot possibly have any protective effect).

But here it may be proper to make a distinction. All absolute governments must very much depend on the administration; and this is one of the great inconveniences attending that form of government. But a republican and free government would be an obvious absurdity, if the particular checks and controuls, provided by the constitution, had really no influence, and made it not the interest, even of bad men, to act for the public good. Such is the intention of these forms of government, and such is their real effect, where they are wisely constituted.

Smith’s views on the national debt and unbalanced budgets in particular revealed the full vigor of his opposition to mercantilists like [Sir James] Steuart. In issuing debt, governments deprived industry and commerce of capital and thereby caused an increase in current consumption. This was to the detriment of accumulation and growth. Unbalanced budgets were a menace to liberty. Once the sovereign developed a taste for borrowing he would realize an increase in his political power since he would no longer be so dependent on tax exactions.

Smith’s views on the national debt and unbalanced budgets in particular revealed the full vigor of his opposition to mercantilists like [Sir James] Steuart. In issuing debt, governments deprived industry and commerce of capital and thereby caused an increase in current consumption. This was to the detriment of accumulation and growth. Unbalanced budgets were a menace to liberty. Once the sovereign developed a taste for borrowing he would realize an increase in his political power since he would no longer be so dependent on tax exactions. The tendency to count as wins for the president new terms for trade that, by any economic measure, are clearly losses for American businesses, workers, and consumers is a function of a pervasively cynical political atmosphere in which triumphs are based on the achievement of what is sought rather than on the actual merits of the result. Trump has “won” on trade because some countries have capitulated and other countries do not have the economic leverage to challenge the United States one-on-one, not because what he has supposedly won is worth winning for the American people and the American economy. Sought though it may be, trade protectionism is a form of slow economic suicide for the country that pursues it.

The tendency to count as wins for the president new terms for trade that, by any economic measure, are clearly losses for American businesses, workers, and consumers is a function of a pervasively cynical political atmosphere in which triumphs are based on the achievement of what is sought rather than on the actual merits of the result. Trump has “won” on trade because some countries have capitulated and other countries do not have the economic leverage to challenge the United States one-on-one, not because what he has supposedly won is worth winning for the American people and the American economy. Sought though it may be, trade protectionism is a form of slow economic suicide for the country that pursues it. Both Hume and Smith assail the mercantilist Weltanschauung of a zero-sum international marketplace with rigidly limited opportunities, inevitably leading to the presumption that one nation’s gain is another nation’s loss. Both forcefully expounded the opposing contention that international trade is mutually beneficial or positive-sum in nature: home employment and national wealth are fostered, not endangered, by free trade.

Both Hume and Smith assail the mercantilist Weltanschauung of a zero-sum international marketplace with rigidly limited opportunities, inevitably leading to the presumption that one nation’s gain is another nation’s loss. Both forcefully expounded the opposing contention that international trade is mutually beneficial or positive-sum in nature: home employment and national wealth are fostered, not endangered, by free trade. The flattering prospects of an extensive commerce freed from British restrictions, and the honours and emoluments of office in independent states now began to glitter before the eyes of the colonists, and reconciled them to the difficulties of their situation.

The flattering prospects of an extensive commerce freed from British restrictions, and the honours and emoluments of office in independent states now began to glitter before the eyes of the colonists, and reconciled them to the difficulties of their situation.