David Henderson writes in the Wall Street Journal about the 2025 winners of the Nobel Prize in economics. Two slices:

The most important issue in economics is growth. That’s why Monday’s announcement of three winners of the 2025 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences is heartening. The Nobel committee awarded it to three economists “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth.” The winners are Dutch-born American-Israeli Joel Mokyr of Northwestern University and Tel Aviv University, Frenchman Philippe Aghion of the Collège de France, Insead in Paris and the London School of Economics and Political Science, and Canadian Peter Howitt of Brown University. Mr. Mokyr won half of the approximately $1.16 million award, while Messrs. Aghion and Howitt will share the other half.

Mr. Mokyr is an economic historian who has focused on understanding why we got the so-called hockey stick of human prosperity, a metaphor in which the long, flat shaft represents centuries of economic stagnation before the Industrial Revolution and the short, sharp blade represents sustained growth in gross domestic product and in GDP per capita in the U.S. and much of Europe after the revolution. Messrs. Aghion and Howitt have focused on theoretical modeling of economic growth, enabling us to understand how various factors interact to bring about growth. Their work complements Mr. Mokyr’s.

…..

Each year, I wait with trepidation to see who has won the Nobel Prize in economics. Many economists seem to want the prize to be given for complex models that don’t matter much. When I saw who won it on Monday, I was happy. Economic growth is the reason extreme poverty has become much rarer around the world, life expectancy has increased dramatically, and most Americans now own many things that were unobtainable luxuries decades ago. All three winners recognized that because economic growth is crucial, we need to understand how we got it and how we can keep it.

Also writing about this year’s economics Nobelists is Reason‘s Billy Binion. A slice:

Together, the trio had explained how innovation drives economic growth, the academy said, when economic stagnation had been the rule, as opposed to the exception, for the vast majority of human history. As a result of that upswing, countless people have been lifted out of poverty.

For his part, Mokyr’s work has focused on the intersection of economics, culture, and history, emphasizing both the importance of understanding why various technologies work if they are to successfully build on each other, as well the affluence that comes from openness to new ideas. In reviewing Mokyr’s 2016 book, A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy, the classical liberal economist Deirdre McCloskey wrote that Mokyr “is a Nobel-worthy economic scientist, right down to his wingtip shoes.

GMU Econ alum Jeremy Horpedahl responds to an uninformed tweet about Joel Mokyr and China: (HT Scott Lincicome)

Mokyr literally has a 500-page book titled Two Paths to Prosperity: Culture and Institutions in Europe and China coming out next month. His first “big ideas” book, The Lever of Riches, has a full chapter exploring why China didn’t have an Industrial Revolution like Europe. He continued to investigate this question throughout his career, such as Part V of his 2018 book A Culture of Growth.

Robert Whaples reviews Andrew Leigh’s The Shortest History of Economics. Two slices:

As Leigh explains in the introduction, the “secret of our discipline is that the most powerful insights come from a handful of big ideas that anyone can comprehend” (5). Three of these are straight out of Intro to Econ and/or Adam Smith: incentives really matter; specialization leads to big productivity gains; and as specialization flourishes, trade becomes invaluable. The fourth is that the “big events are rarely driven by sudden shifts in norms or culture” (7) but more often by new technologies or changing policies. A couple of notable economic historians would dispute this. In A Culture of Growth, for example, Joel Mokyr argues that the primary driver of the Industrial Revolution was a cultural shift towards valuing and disseminating useful knowledge. In Bourgeois Dignity, D. N. McCloskey makes a similar argument—that the unprecedented economic growth of the modern era was primarily due to a shift in societal values and rhetoric, particularly the rise of liberalism and the revaluation of the “bourgeois” virtues. Leigh might reply that these changes weren’t “sudden,” but in the long history of humanity which this book covers they do appear to be rather sudden. Instead of grappling with these critical ideas about what sparked the “Great Enrichment,” Leigh’s chapter on “The Industrial Revolution and the Wealth of Nations” tells a much simpler and more compact story. It brings in important ideas from Adam Smith, Jeremy Bentham, William Stanley Jevons, John Stuart Mill and even Frédéric Bastiat—along with interesting thoughts on the importance of clocks and mirrors, among other things. Writing a short history like this is a delicate balancing act. Another balancing act is temporal. The chronological plot of The Shortest History moves very quickly at first, before decelerating. One senses that Leigh really cares much more about the present, its immediate roots, and his agenda for the future. Surprisingly, to me at least, it takes only fifteen short pages to get from the dawn of humankind to the year 600 AD and we zip to the beginning of the twentieth century in another forty-eight pages.

…..

However, a far more glaring omission comes in Leigh’s discussion of the Great Depression—which, like much else in the book, is very US-centric (despite the fact that the publisher is British and the author is Australian). The narrative of the Great Depression opens with and stresses the stock market crash and brings in other causes like the paradox of thrift, the Smoot-Hawley tariff, and immigration policy. It omits mention of weaknesses in the banking sector due to unit-banking laws, the contraction of the money supply, the missteps of the Federal Reserve, and problems with interwar gold standard as emphasized by Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz in their Monetary History of the United States and Barry Eichengreen in Golden Fetters. These omissions border on malpractice. Did Leigh throw away the memo when Ben Bernanke said, “Regarding the Great Depression . . . we did it. We’’e very sorry. . . . We won’t do it again”?

In addition, Leigh doesn’t address why the Great Depression persisted so long. He could have mentioned Robert Higgs’s arguments about “regime uncertainty,” paralyzing investors or at least discussed a few of the policies that stifled the recovery, especially the National Industrial Recovery Act. He certainly has room to do so. In a one-page box on Sadie Alexander, the first African American woman to receive a doctorate in economics, Leigh mentions her criticisms of the NIRA, which “boosted wages in certain sectors” so that “employers in those industries fired black workers and hired whites in their place” (96). But he doesn’t mention that the above equilibrium wages of the National Recovery Administration caused overall employment to collapse and pushed up prices causing sales to fall as shown by economic historians like Jason Taylor. The fuller story simply clashes too much with his overall thrust that government solves problems like these. (The chapter also repeats the conventional wisdom that Weimar Germany was crippled by enormous reparations under the Treaty of Versailles. This argument is contested by Max Hantke and Mark Spoerer in “The Imposed Gift of Versailles: The Fiscal Effects of Restricting the Size of Germany’s Armed Forces, 1924–29.” They find that the net effect of the Treaty’s stipulations on the German central budgets was either much lower than previously thought or even positive, as reductions in military spending offset all or more than all of the reparations bill.)

The irony is that Democrats who tried so hard to get rid of the filibuster under President Joe Biden are now taking advantage of it. Joe Manchin (West Virginia) and Kyrsten Sinema (Arizona) stopped Democrats from “going nuclear” in 2022 — and were effectively forced into retirement. Perhaps Democrats will have the votes to nuke the filibuster the next time they control the Senate, but they’d prefer if Republicans did it for them.

Juliette Sellgren talks with Derek Scissors about China’s economic policy.

Travis Fisher details “some inconvenient truths for climate radicals.”

Gabriela Calderon de Burgos and Marcos Falcone urge Argentina to dollarize.

Enforcing protective measures generally requires a large bureaucracy.

Enforcing protective measures generally requires a large bureaucracy. The people who are most anxious to obstruct changes in the channels of trade which are coming about of themselves because they are profitable, are often extremely anxious to promote changes which will not come about of themselves because they are not profitable.

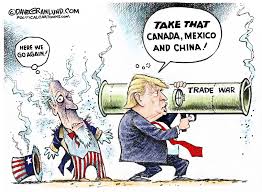

The people who are most anxious to obstruct changes in the channels of trade which are coming about of themselves because they are profitable, are often extremely anxious to promote changes which will not come about of themselves because they are not profitable. For more than a century, the United States has been the most prosperous country in the world. Americans represent just 4.2% of the global population yet they produce more than 26% of global GDP. US median income is nearly nine times the global average and the US poverty rate is a fraction of the global rate. This prosperity was built on a foundation of economic freedom. And that freedom is eroding thanks to President Trump’s trade war.

For more than a century, the United States has been the most prosperous country in the world. Americans represent just 4.2% of the global population yet they produce more than 26% of global GDP. US median income is nearly nine times the global average and the US poverty rate is a fraction of the global rate. This prosperity was built on a foundation of economic freedom. And that freedom is eroding thanks to President Trump’s trade war.