There’s a lot to like in Richard Jordan’s recent essay at Law & Liberty, “Romancing Creative Destruction.” But it’s also infected with a notable flaw, namely, Jordan’s claim, complete with added emphasis, “capitalism is soulless.”

Read narrowly, this assertion is empty of useful meaning. Capitalism isn’t a sentient creature; it has neither consciousness nor a conscience. Capitalism is the name we give to a particular manner of human interactions. It therefore is no more useful to observe that “capitalism is soulless” than it is to observe that “automobile traffic is soulless.”

But the ‘soullessness’ of capitalism is claimed so very frequently, and by people of all ideological stripes, that this claim obviously conveys some substantive meaning to those who encounter it.

What might that meaning be? I think I know. The claim that capitalism is soulless reflects a confusion of “impersonal” with “soulless.” Capitalism does indeed feature myriad impersonal exchanges, but this reality doesn’t mean that capitalism is soulless.

…..

In small communities, the members of which seldom interact with individuals whom they do not know personally, all commercial interactions feature heavy doses of personal knowledge and emotion. Tailor Smith knows that grocer Jones will not cheat him because Smith and Jones are old friends. While each gains economically from trading with the other, each also gains emotionally. Smith treasures his in-store chit-chat with Jones, who in turn appreciates Smith’s purchase of that extra loaf of bread – a purchase motivated, Jones is silently aware, by Smith’s knowledge that Jones is currently going through a financial rough patch.

These interactions are personal. And they are good.

Trade exclusively among people who know each other – even when wholly unregulated by government – is not, as such, capitalism. Capitalism requires more than that government remain largely uninvolved in the details of economic processes; capitalism also involves (1) such an openness to economic change that incessant innovation is encouraged, and (2) an eagerness to earn profits by catering to as many people – and as diverse a population of people – as possible. Under capitalism, the division of labor – that is, specialization – is limited not by individuals’ personal connections or by boundaries fixed by tradition, but (as Adam Smith famously observed), “by the extent of the market.”

The greater the number of people who interact economically with each other, the greater the ability of individuals as producers to specialize. This increased specialization, in turn, increases output per person. But the same condition that makes it possible for this increased specialization to occur also makes it impossible for any individual in this economy to know personally all the other individuals with whom he economically interacts. Because in today’s global economy the people with whom we interact economically number literally in the billions, the percentage of these persons with whom we also interact personally is near zero.

It is therefore true that almost all of the motives that prompt and guide the billions of human actions that daily make possible our modern prosperity are exclusively ‘economic’ rather than warm and personal. Whoever it was who rolled out of bed one morning a few weeks ago to drive from farm to slaughterhouse the pig that I shared on Christmas day with family and friends does not know me, and I don’t know him. That person certainly contributed to my fine Christmas dinner, but the motivation wasn’t love or neighborliness. And no part of the purchase of the ham that I ate was motivated by affection for that truck driver – or, indeed, for anyone else involved in supplying that ham. From start to finish, the motivation and information came in the form of prices, wages, profits, and losses registered in terms of money. All of these exchanges were purely ‘economic.’ The chief motivation throughout is material gain, and the whole process is guided by rational, monetary calculations. Almost no role was played by personal, warm fellow-feelings.

All true. Yet to describe capitalism – or, at least, capitalist society – as soulless is misleading.

First of all, capitalism doesn’t prevent us from exercising and experiencing fellow-feeling. We denizens of the 21st-century global economy have just as much opportunity to connect personally with fellow human beings as did our ancestors in the Pleistocene and those in quaint 18th-century New England villages. And, of course, many of us do. We love our parents, siblings, children, and grandchildren. We are members of churches. We care for our neighbors. We comfort our friends when they are down and are comforted by them when fortunes are reversed. If some of us today choose to live lives more isolated and alone – an option admittedly made easier by capitalist riches – that isn’t the fault of capitalism. If fault must be assigned, it is on the individuals who choose that option.

Yet, again, most of us don’t choose to live as isolated atoms. I suspect that the typical resident today of Manhattan or Miami or Manchester has as many personal, warm connections with other flesh-and-blood individuals as did the typical resident 500 years ago of any medieval village.

But the charge that capitalism is “soulless” is flawed in a second and even deeper way. What the denizen of modernity has that his medieval ancestor lacked are very real connections also to countless more fellow human beings. In today’s globe-spanning system of social cooperation, billions of individuals every day are incited and guided to work for each other’s betterment. We still have the personal connections from which we draw warmth. But we also have extensive market connections to countless strangers that allow vast swathes of humanity to assist each other as if each of us loves, and is loved, by billions of strangers of diverse backgrounds and beliefs.

All of this goes to show that without the initiative that comes from immediate responsibility, ignorance will persist in the face of masses of information however complete and correct…

Today it is possible, even in our most prestigious educational institutions at all levels, to go literally from kindergarten to a Ph.D. without ever having read a single article – much less a book – by someone who advocates free-market economics or who opposes gun control laws. Whether you would agree with them or disagree with them, if you read what they said, is not the issue. The far larger issue is why education has so often become indoctrination.

Today it is possible, even in our most prestigious educational institutions at all levels, to go literally from kindergarten to a Ph.D. without ever having read a single article – much less a book – by someone who advocates free-market economics or who opposes gun control laws. Whether you would agree with them or disagree with them, if you read what they said, is not the issue. The far larger issue is why education has so often become indoctrination. Yet Friedman did not simply propose technical fixes to policy problems. He set his economic ideas within a broader philosophy of individual freedom that served as the moral foundation of his work.

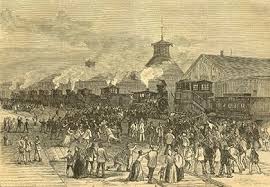

Yet Friedman did not simply propose technical fixes to policy problems. He set his economic ideas within a broader philosophy of individual freedom that served as the moral foundation of his work. The record is a litany of failure of employer attempts to keep wage costs down by importing labor. In 1828 the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company sent agents to Belfast and Cork, to the Upper Rhine, and to Liverpool. It hired workers well below prevailing rates. But a year later the company president was forced to report that while “the rise of wages of labor was for some time controlled, and for a few months sensibly reduced by the importation of those laborers and artificers from Europe … difficulties of enforcing under existing laws the obligations of the emigrants and of preserving among them due subordination” made it unlikely that the company could again rely on such methods to restrict wage increases.

The record is a litany of failure of employer attempts to keep wage costs down by importing labor. In 1828 the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company sent agents to Belfast and Cork, to the Upper Rhine, and to Liverpool. It hired workers well below prevailing rates. But a year later the company president was forced to report that while “the rise of wages of labor was for some time controlled, and for a few months sensibly reduced by the importation of those laborers and artificers from Europe … difficulties of enforcing under existing laws the obligations of the emigrants and of preserving among them due subordination” made it unlikely that the company could again rely on such methods to restrict wage increases.