By the way, protectionist policies are not inflationary. They distort relative prices, but don’t cause overall increases. If you want to know who to blame for rising prices, look at the Federal Reserve.

Next, we have Trump claiming that he’s reduced red ink.

Joe Biden handed me a catastrophically high budget deficit… But with the help of tariffs, we have cut that federal budget deficit by a staggering 27% in a single year

This is another easily debunked assertion.

The budget deficit was just as high in 2025 as it was in 2024, as shown by this data from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

“On fuel costs, Californians in particular are getting hosed” – so reports the Washington Post‘s Dominic Pino. Three slices:

The most obvious place to start in explaining California’s problem is its gas tax. At 70.92 cents per gallon, it was the highest of any state in 2025, and more than double the median state. But Illinois was only 4.5 cents behind, and its prices were nowhere near California’s.

California and Washington are the only two states with economy-wide cap-and-trade programs. California’s program raises the price of gasoline by forcing gasoline suppliers to buy allowances. Those higher costs are eventually passed on to drivers. The California Legislative Analyst’s Office estimates that cap-and-trade raises the retail price of gasoline by 23 cents per gallon.

…..

California also does not have any inbound pipelines for crude oil or gasoline that connect to the rest of the country. Its imports primarily arrive by ship. The Jones Act, a protectionist federal law that covers shipping within the United States, makes it uneconomic to transport oil or gasoline from the Gulf Coast region to California.

…..

In the meantime, Californians will continue to pay far more for gasoline than just about anyone else in America. And for what? The state’s share of commuters who use public transportation is slightly below the national average. As wealthier Californians switch to electric vehicles and pay nothing for gas, poorer people who can’t afford a new car are shouldering a growing burden. And even if California eliminated all of its greenhouse-gas emissions from passenger vehicles, it would account for only 0.2 percent of the world’s total GHG emissions.

Next time Sacramento politicians want to complain about price-gouging at the pump, they need to look in the mirror. Other states aren’t having this problem.

The United States faces a choice at this pivotal moment. Withdrawing completely, as the Trump administration has said it will do, means surrendering influence over the IPCC’s direction — ceding control to alarmists, adversaries and less rigorous voices. The result will be more politicized exaggeration, more scare stories and more global alarmism.

Instead, the U.S. should remain, engage and wield outsize leverage as the IPCC’s largest funder. This would be remarkably cheap. In 2024, the U.S. paid around $1.9 million to cover more than a quarter of the IPCC budget, dwarfing China’s paltry $23,000 contribution the same year.

The problem, as we have learned, is that Border Patrol is a very different job from urban policing. There are no crowds of protesters getting in your way on the southern border. Nor are there many private residences that you need to enter when pursuing suspects, or a lot of U.S. citizens going about their day who could be confused for illegal immigrants.

By the nature of their day job, CBP agents are simply not trained to operate in dense urban areas as ICE traditionally is. If the administration keeps sending them into U.S. cities anyway, we shouldn’t be surprised if complications keep arising.

Even coming from an ordinary politician, this federal takeover would be a terrible idea. The Constitution entrusts the administration of federal elections to the states and localities, subject to Congress’s passage of laws regulating the manner of election. Congress has rightly respected the states’ and localities’ lead role, and it should go on doing so.

Jacob Sullum ponders the Trump administration’s disrespect for Americans’ Second Amendment rights. A slice:

“I don’t care if you have a license in another district, and I don’t care if you’re a law-abiding gun owner somewhere else,” [Jeanine] Pirro said on Fox News. “You bring a gun into this district, count on going to jail, and hope you get the gun back.”

That broad threat is hard to reconcile with the right to bear arms recognized by the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen which said states may not require that people demonstrate a “special need” to carry guns in public for self-defense.

Although Sorkin does an excellent job of describing the main characters in the narrative, he fails to fully understand and convey the fundamental causes of the crash and depression. He overplays the role of speculation leading up to the market crash in October 1929; largely ignores the monetary causes of the deep depression, in which the stock of money fell by one-third between 1929 and 1933; and never addresses the flaws in the “Real Bills Doctrine” that misguided monetary policy. There is no mention in the book of: (1) the path-breaking work of Clark Warburton, who, in the mid-1940s and early 1950s, provided a detailed analysis of the monetary causes of business fluctuations [see Warburton 1966: Depression, Inflation, and Monetary Policy: Selected Papers, 1945–1953]; (2) Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s monumental Monetary History of the United States [1963]; or (3) Thomas Humphrey and Richard Timberlake’s Gold, The Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed: Sources of Monetary Disorder, 1922–1938, which appeared in 2019.

Phil Gramm, former chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, calls the Humphrey-Timberlake (H‑T) book “the most important book written on the Great Depression” since Friedman and Schwartz’s Monetary History. According to Gramm, “The book points to an obscure and largely forgotten theory, the Real Bills Doctrine, as the culprit for the failure of the Federal Reserve … to respond to the collapse of the money supply, which turned a financial panic into a Great depression” (from the front matter in H‑T). It is a shame that Sorkin was unaware of this 201-page book.

Jay Parsons tweets: (HT Scott Lincicome)

Narrative buster: The share of U.S. single-family homes occupied by renters is at 15+ year LOWS, according to Redfin.

And yet both sides of the aisle want you to believe institutional investors are the boogeyman turning America into a renter nation… 🙄

The perpetuity of self-government depends on the sound political sense of the people, and sound political sense is a matter of habit and practice. We can give it up and we can take instead pomp and glory.

The perpetuity of self-government depends on the sound political sense of the people, and sound political sense is a matter of habit and practice. We can give it up and we can take instead pomp and glory. In a growing economy there is more pie to go around – enabling everyone to have a bigger slice and without the interference of government redistribution programs.

In a growing economy there is more pie to go around – enabling everyone to have a bigger slice and without the interference of government redistribution programs. International trade, especially, tends to expose cultures to new ways of doing things and breaks down the perception that only one way is possible, even in non-economic areas like politics, art and religion.

International trade, especially, tends to expose cultures to new ways of doing things and breaks down the perception that only one way is possible, even in non-economic areas like politics, art and religion.

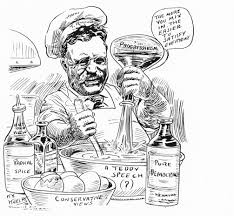

Because ideology and political movements develop reciprocally, the pervasive reactions to the rise of big business around the turn of the twentieth century gave rise not simply to a proliferation of newly organized interest groups seeking government protection of threatened positions; it also prompted intellectuals, both independents and “hired guns,” to develop new rationales for more active government. Thus Progressivism as ideology developed concurrently with Progressivism as politico-economic practice, each aspect reflecting the changing socioeconomic opportunities and hazards created by the rise of big business and its repercussions throughout the economy.

Because ideology and political movements develop reciprocally, the pervasive reactions to the rise of big business around the turn of the twentieth century gave rise not simply to a proliferation of newly organized interest groups seeking government protection of threatened positions; it also prompted intellectuals, both independents and “hired guns,” to develop new rationales for more active government. Thus Progressivism as ideology developed concurrently with Progressivism as politico-economic practice, each aspect reflecting the changing socioeconomic opportunities and hazards created by the rise of big business and its repercussions throughout the economy.