Scott Lincicome points out that “trade is among people — and retaliation can be, too.” Two slices:

Recently, however, we’ve seen the flipside of this policy lesson, as foreign individuals have increasingly abstained from buying American goods and services in response to U.S. government policies—mainly tariffs—and rhetoric. This reaction, which spans several countries and industries, is particularly interesting since retaliation is one area of trade that’s rightly focused on government action—because it’s typically governments doing the retaliating. Now, however, private individuals are pushing back against the United States—and, perhaps surprisingly, they might be imposing significant aggregate harms on the U.S. economy.

The clearest example of this trend is in the U.S. tourism industry, which has seen a noteworthy decline in foreign visits to the United States since the beginning of the year. According to Axios, for example, international arrivals at the 10 busiest U.S. airports have declined 7 percent this year versus last, and travel research firm Tourism Economics expects an 8.2 percent drop for the whole year—an annual total that’s well below pre-pandemic (2019) levels.

…..

Dig around and you’ll find plenty more instances of private retaliation this year. Heightened nationalism and anti-American sentiment accelerated Chinese consumers’ shift from Apple’s iPhones to homegrown alternatives. Levi’s recently warned in a U.K. filing that “rising anti-Americanism as a consequence of the Trump tariffs and governmental policies” could cause British shoppers to avoid its clothing. And following Trump’s 50 percent tariffs this August, Indians have called for boycotts of popular U.S. brands like Pepsi, Subway, and KFC.

Of course, not all financial struggles of U.S. multinationals abroad—and U.S. exporters at home—should be attributed to people mad about Trump administration policies. Some of it stems from internal or market problems or, in the case of China and (to a lesser extent) Canada, government restrictions on U.S. goods and services. (Canadian provinces’ alcohol bans are proving particularly painful.) Yet governments in most of these markets haven’t retaliated, and it’s clear from loads of reporting that people abroad are protesting with their pocketbooks—whether because they’re mad about U.S. policy or because they simply need to hedge their business bets in a highly uncertain global trade environment. It’s also clear, moreover, that many other private responses are too small or hidden to be reported. A recent Washington Post piece, for example, included a random aside about a New York-based gear manufacturer facing a tough export market not because of foreign tariffs but simply because “international inquiries have dried up by about 50 percent … as buyers in other countries look for ways to bypass American manufacturers.” Whether those buyers are acting out of anger or strategy doesn’t really matter—what matters is that they’re acting, that they’re doing so in response to U.S. policy they don’t like, and that there are probably many more companies and people abroad doing the same.

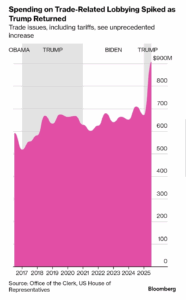

The most predictable result of tariffs isn’t higher prices; it’s more lobbying. And that’s just what we got – in unprecedented fashion:

When politicians interfere in private markets and industry, crazy things happen. So it goes with President Trump’s rolling attempt to play Pharmacist in Chief on drug production, government approvals, and consumer access and prices.

…..

Meanwhile, Mr. Trump on Tuesday announced a deal that gives Pfizer a three-year reprieve from his mooted 100% tariffs on imported pharmaceuticals. In return, Pfizer will sell medicines to Medicaid at a price that matches the lowest paid in the developed world—the so-called most-favored-nation price.

This is a good short-term deal for Pfizer since federal law already requires companies to sell drugs to Medicaid at huge discounts. Pfizer’s stock popped 6.8% Tuesday and another 6.8% Wednesday on the news. Drug stocks have underperformed this year under the threat of Mr. Trump’s tariffs and price controls.

It’s hard to begrudge Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla for buying political goodwill from the President to reduce punitive costs for his company. But the deal has caused an uproar in the industry, as every CEO must now decide whether to ask Mr. Trump for a similar most-favored-company deal.

The White House is leaking to the press that any company that refuses such a deal will get hit with punitive tariffs and price controls. This is a form of political extortion akin to what Democrats did with their pharma price controls in the Inflation Reduction Act. The real winners in all this are in China, which is bidding to replace the U.S. as the home of the world’s leading biotech and pharma industry.

The federal government just accumulated an additional $2 trillion in debt over the last 12 months. That’s the kind of debt surge America usually racks up in wartime or during major national emergencies. But today, as Republicans and Democrats engage in another budget-driven shutdown drama, we are not at war. There is no pandemic. The economy is humming. And another shutdown is happening. Yet it will solve nothing about the fact that the political class is burning through money at a pace that would make former President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s war cabinet blush.

The Daily Treasury Statement shows total federal debt rising from $35.5 trillion last September to $37.5 trillion this week. In peacetime, with unemployment low and the stock market booming, that’s breathtakingly reckless. Yet in Washington, winning at politics matters more than confronting the cause of the problem: relentless overspending, and especially the explosion of entitlement programs.

Republicans, despite their fiscal-hawk branding, have presided over much of this surge. They boast $206 billion in Department of Government Efficiency “savings” and $213 billion in tariff receipts—rounding errors when compared with the debt. As the Tax Foundation’s Alex Durante and Garrett Watson point out, tariff revenue does almost nothing to change the country’s fiscal trajectory.

George Will writes about Philip K. Howard’s new book, Saving Can-Do. Two slices:

He also is a genteel inveigher against the coagulation of American society, which is saturated with law. In his new book “Saving Can-Do: How to Revive the Spirit of America,” he argues that law’s proper role is preventing transgressions by authorities, not micromanaging choices so minutely that red tape extinguishes individual responsibility and the social trust that individualism engenders.

…..

Howard also notes that merely raising a roadway on a Port of Newark bridge required five years and 20,000 pages of environmental assessments, including the impact on historic buildings within a two-mile radius (no buildings, historic or otherwise, were affected), and required input from Native American tribes around the country whose ancestors might have lived at Newark’s harbor. The 1956 statute authorizing the interstate highway system was 29 pages long.

Building a small, $200,000 public toilet in San Francisco was budgeted to cost $1.7 million because approval had to be won from, among many other agencies, the city’s Arts Commission. The fragile Hudson River rail tunnels connecting Manhattan to everywhere west were built between 1906 and 1910 by our great-grandfathers. New tunnels are expected in 2038, 29 years after construction was announced.

K-12 schools micromanaged by multi-hundred-page collective bargaining agreements with teachers unions “more closely resemble penal institutions” than centers for nurturing, Howard writes. “The disempowerment of school leaders” by union rules in the past 50 years “is the main reason bad schools get worse, and why mediocre schools rarely improve.”

GMU Econ alum Erik Matson reviews Glory Liu’s Adam Smith’s America.

Eugene Volokh’s letter in today’s Wall Street Journal is great:

Three cheers for your editorial “Charlie Kirk, Free Speech and the Right” (Sept. 29), about the University of South Dakota’s planned firing of an art professor for a vulgar social-media post. If we have any interest in promoting a culture of free debate at U.S. universities, even foolish and tasteless speech needs to be protected.

This incident, and others like it, seems to stem from what one might call “censorship envy”—the tendency to see others successfully suppressing speech they dislike and to react by wanting to do likewise. It’s understandable that some on the right would feel compelled to do so once they’re in power. But the consequence, as you note, is simply a further spiral of suppression, emboldening the left to stick to its illiberal ways.

Nor can this sort of punishment spiral be easily limited. The South Dakota professor’s post was unprofessional and largely substance-free, but we can’t trust universities to draw such lines fairly and evenhandedly. And when students see that even their tenured professors can be fired for speech, they will rightly worry that they can also be expelled or suspended for their statements.

The university should be about discussion and debate with ideas—even immaturely expressed ones—responded to by other ideas, not with violence, firing or expulsion. That’s true when the left tries to restrict right-wing ideas, and equally so when the shoe is on the other foot.