In the pre-COVID era, the public health establishment had been gradually falling under the sway of progressives pushing their agendas, but it retained enough integrity to heed serious scientists—the ones who crunched data from past pandemics and analyzed studies of viral transmission and disease mitigation. They debated the efficacy of prevention measures, weighing the benefits against the costs, as the renowned epidemiologist Donald Henderson did in a landmark paper in 2006 contemplating a pandemic as deadly as the 1918 Spanish Flu (Inglesby, Nuzzo, O’Toole, and Henderson, 2006). Henderson, who had directed the successful international effort to eradicate smallpox, considered measures like closing businesses and schools, prohibiting social gatherings, restricting travel, mandating social distancing, quarantining those exposed to infection, and encouraging the universal wearing of surgical masks. His paper advised against all those measures, warning that they would do little to stop the spread but could be “devastating socially and economically” (2006: 368).

“Experience has shown,” Henderson and his colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh wrote, “that communities faced with epidemics or other adverse events respond best and with the least anxiety when the normal social functioning of the community is least disrupted” (2006: 373). The researchers stressed the need for leaders to “provide reassurance” to the public, and specifically cautioned them not to be guided by mathematical models of the pandemic, warning that such models could not reliably predict either the spread of the disease or the consequences of measures like closing businesses and schools.

This sensible advice was incorporated into pre-2020 pandemic plans developed by the Public Health Agency of Canada, the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and the United Kingdom’s Department of Health. The UK plan flatly declared, “It will not be possible to halt the spread of a new pandemic influenza virus, and it would be a waste of public health resources and capacity to attempt to do so” (UK Department of Health, 2011: 28.) The CDC’s planning scenarios didn’t recommend extended school or business closures even if the fatality rate were as high as during the Spanish Flu (Qualls, Levitt, Kanade, et al., 2017: table 8), and the other agencies reached similar conclusions. None of them urged universal masking, either, because randomized clinical trials had shown that, contrary to popular wisdom in some Asian countries, there was “no evidence that face masks are effective in reducing transmission,” as the World Health Organization (WHO) summarized the scientific literature (WHO, Global Influenza Programme, 2019: 14). Canada’s plan for a pandemic specifically rejected masks as well as efforts to disinfect surfaces in public areas (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2006).

But then, suddenly, all that peer-reviewed evidence and sensible advice was discarded. Instead of reassuring the public, public health officials went into full panic mode when a team of researchers at Imperial College in London released a computer model in March of 2020 projecting that within three months there would be 30 COVID patients for every one bed in the intensive-care units of hospitals in Great Britain (Ferguson, Laydon, Nedjati-Gilani, et al., 2020). This, of course, was precisely the sort of mathematical model that Henderson had warned against—and this model was based on obviously unrealistic assumptions. Yet public health leaders in Europe and North America immediately embraced not only the doomsday numbers but also the modelers’ conclusion that the “only viable strategy” was to impose drastic restrictions on businesses, schools, and social gatherings until a vaccine became available.

The Imperial College team gave no reason to reject the conclusions of scientists with far more expertise who had spent years devising plans for a pandemic. The modelers didn’t even pretend to weigh the costs and benefits of a lockdown, and neither did the public health officials who adopted the policy. Their sole justification was the Chinese government’s claim that its lockdown had halted COVID. Given the communist government’s history of skewing and suppressing public health data, there was every reason to doubt this claim—and no reason to look to China’s authoritarian decrees as a model for policy in a free society.

Yet lockdowns immediately became “the science,” and those who questioned this “consensus” were denounced despite their sterling credentials. One of the first victims was John Ioannidis of Stanford University, whose studies of the reliability of medical research had made him one of the world’s most frequently cited authors in the scientific literature. Early in the pandemic he published an essay presciently titled, “A Fiasco in the Making? As the Coronavirus Pandemic Takes Hold, We Are Making Decisions Without Reliable Data” (Ioannidis, 2020, March 17). He echoed the longstanding concerns of Henderson and other experts, but was immediately savaged on Twitter and in the media by scientists and journalists accusing him of endangering lives. “I was very disappointed to see these attacks coming from knowledgeable people,” he said. “Scientists whom I respect started acting like warriors who had to subvert the enemy” (Tierney, 2021).

…..

Thousands of scientists and doctors went on to sign the Great Barrington Declaration, and they were vindicated as the pandemic wore on. The lockdown strategy failed, both in China—its “Zero COVID” strategy was a social and economic disaster—and in the rest of the world. Except in a few isolated spots, the lockdowns didn’t halt the spread, as demonstrated by dozens of studies and by the relative success of places that ignored the “consensus.” Sweden, Finland, Norway, and the state of Florida kept schools and businesses open, without mask mandates, while doing as well as or better than average in measures of age-adjusted COVID mortality and overall “excess mortality.”

But “the science” continued to trump actual science in most other places. The Great Barrington scientists were espousing longstanding principles of public health and had plenty of new data on their side, but the lockdown advocates had powerful allies in the media as well as in the public agencies and private foundations funding much of the infectious-disease research around the world. Early in the pandemic prominent virologists privately expressed concern that the coronavirus had been created in a laboratory in Wuhan, but then they publicly dismissed that possibility after a teleconference with the chief scientific advisers to the UK and the US governments—governments that also just happened to be funding some of the virologists’ research.

…..

The British Medical Journal (BMJ), published a scurrilous ad hominem attack on the Great Barrington scientists, absurdly accusing them of being somehow linked to “climate denialists,” the libertarian billionaire Charles Koch, and the fossil fuel industry (Yamey and Gorski, 2021, September 13). Bill Gates, whose foundation was a major source of research funding, dismissed the “crackpot theories” of another prominent lockdown opponent, Scott Atlas of the Hoover Institution at Stanford, and the Stanford faculty senate passed a resolution declaring Atlas’ actions to be “anathema to our community” (Chesley, 2020, November 20). The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), published an article recommending that Atlas and other doctors who publicly criticized COVID orthodoxy should lose their medical licenses, and the General Medical Council of Britain actually restricted the privileges of one doctor who did so (Pizzo, Spiegel, and Mello, 2021, February 4).

…..

The scientists gave in to the fearmongers because the scientific and public health establishments had been gradually weakened by a preexisting pathology. Their collapse during the pandemic came suddenly, but it was the culmination of what Marxists call the long march through institutions—more specifically, what I call the Left’s war on science (Tierney, 2016). For more than a century, from the eugenics movement of the 1920s through today’s “climate emergency,” progressives have been using their cherry-picked versions of “the science” to justify their plans for redesigning society. As they’ve come to dominate universities, professional societies, scientific journals, and the mainstream media, they’ve enforced progressive orthodoxy in one discipline after another, squelching debate by demonizing dissenters on topics like IQ, sex differences, race, family structure, transgenderism, and climate change.

Public health institutions have been especially corrupted, as James T. Bennett and Thomas J. DiLorenzo chronicled two decades ago in their history of the profession, From Pathology to Politics. “Since 1968,” they write, “a top priority—if not the top priority—of the public health establishment has been to promote the idea that more government control and intervention is the surest route to sounder health” (2008: 25). These interventions have often been disastrous, like the past campaigns to restrict fat in the diet, which led to more obesity and diabetes as people substituted carbohydrates. Leading nutrition researchers criticized this intervention as unsupported by evidence, but public health activists prevailed in the public debate by falsely portraying the critics as tools of the food industry.

…..

The public’s trust in scientists rose at the start of the pandemic, but it has since plummeted—and for good reason. The lockdowns were the worst public policy mistake ever made during peacetime. Until scientists and public health officials acknowledge their catastrophic errors and reform their politicized institutions, there’s no reason to trust them anymore.

Of course no one wants money for its own sake: we want it because we can get the things and services which we want by paying it away again.

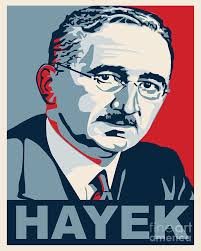

As in the intellectual so in the material sphere, competition is the most effective discovery procedure which will lead to the finding of better ways for the pursuit of human aims. Only when a great many different ways of doing things can be tried will there exist such a variety of individual experience, knowledge and skills, that a continuous selection of the most successful will lead to steady improvement.

As in the intellectual so in the material sphere, competition is the most effective discovery procedure which will lead to the finding of better ways for the pursuit of human aims. Only when a great many different ways of doing things can be tried will there exist such a variety of individual experience, knowledge and skills, that a continuous selection of the most successful will lead to steady improvement. Adam Smith’s decisive contribution was the account of a self-regulating order which formed itself spontaneously if the individuals were restrained by appropriate rules of law. His Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations marks perhaps more than any other single work the beginning of the development of modern liberalism. It made people understand that those restrictions on the powers of government which had originated from sheer distrust of all arbitrary power had become the chief cause of Britain’s economic prosperity.

Adam Smith’s decisive contribution was the account of a self-regulating order which formed itself spontaneously if the individuals were restrained by appropriate rules of law. His Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations marks perhaps more than any other single work the beginning of the development of modern liberalism. It made people understand that those restrictions on the powers of government which had originated from sheer distrust of all arbitrary power had become the chief cause of Britain’s economic prosperity. [M]y concrete differences with socialist fellow-economists on particular issues of social policy turn inevitably, not on differences in values, but on differences as to the effects particular measures will have.

[M]y concrete differences with socialist fellow-economists on particular issues of social policy turn inevitably, not on differences in values, but on differences as to the effects particular measures will have.