This ad for a 1966 American Motors Rambler station wagon features a lot of bragging about the safety features of the car. Among the features that the marketers thought it wise to highlight are lap-only seat belts, visors on top of the windshield, and the side-view mirror on the driver’s side. (Geezers and geezettes of my generation, and of earlier generations, will recall that side-view mirrors on the passenger side of cars were not at all the ubiquitous feature that they are today. This commercial – which was made in the year that I turned 8 – suggests that even driver-side side-view mirrors were not yet common, or at least not universal, on cars zooming along America’s roads in the mid-1960s.)

Bryan Caplan asks a good question – good for considerations of both policy and academic research. And it’s a question that reminds us yet again that contracts – including employment contracts – are made along multiple margins, only some of which are formalized or explicit.

Wisdom – here in the form of sound economics – from Tyler Cowen on immigration.

Here’s a letter to Washington, DC, radio station WTOP:

You report that the U.S. is the “only advanced economy without guaranteed vacation.” The tone of your report, however, mistakenly suggests that this fact harms American workers.

When government mandates vacation time it artificially restricts employers’ ability to compete for employees by offering, in lieu of the minimum number of vacation days mandated by government, other forms of compensation such as higher take-home pay, greater employer contributions to pensions, or more flexible daily work schedules. Therefore, such a mandate reduces workers’ bargaining power over the terms of their employment contracts. Each and every worker – regardless of his or her personal circumstances or preferences – has no option but to accept the vacation terms as dictated by government.

So rather than report in somber tones that the U.S. is the “only advanced economy without guaranteed vacation,” you’d serve the cause of accuracy better by reporting in upbeat tones that the U.S. is the “only advanced economy still to guarantee to its workers the freedom to determine how much vacation time each would like in place of other forms of compensation.”

Sincerely,

Donald J. Boudreaux

Professor of Economics

and

Martha and Nelson Getchell Chair for the Study of Free Market Capitalism at the Mercatus Center

George Mason University

Fairfax, VA 22030

Note that the issue identified in the letter above doesn’t disappear even if we assume, contrary to fact, that firms have substantial monopsony power in hiring workers. As long as there are several dimensions to employment contracts and conditions – take-home pay; a variety of formal fringe benefits (such as employer contributions to workers’ pensions); various aspects of work conditions (such as leniency regarding employees making personal telephone calls while on the clock); being hired (versus not being hired) in the first place – a government mandate that forces firms to offer more worker-friendly terms on one dimension gives even monopsonistic firms incentives to offer only worse-for-workers terms on one or several other dimensions.

In my most-recent column in the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review I discuss the current IRS scandal. Here’s a slice:

The fundamental question raised by the IRS scandal isn’t whether Obama ordered, or even knew of, the apparent misuse of the taxing power to punish political opponents. Rather, the fundamental question asks about the wisdom of creating in the first place government agencies that can so easily abuse their power in order to play political favorites.

In the private sector, we rely upon two core features of markets to protect against such abuse. First, each person is free not to patronize firms that fail to deliver sufficient value. Second, firms prosper only by — and only so long as they continue — competing successfully for consumers’ dollars. But because government agencies are funded with taxes — and because those agencies face no competition — greater reliance than is necessary in the private sector must be put on the integrity, altruism and diligence of elected officials to oversee government agencies in ways that ensure that those agencies don’t abuse their awesome powers.

When, as appears to be the case here, government officials turn out to be mere humans at monitoring the vast legions of government workers under their charge, it is indeed appropriate to blame and to criticize those officials. It is appropriate to blame and to criticize them not for their being human but, instead, for their promising the impossible — namely, for their promising to exercise the superhuman abilities that alone can ensure that government agencies behave with at least as much efficiency and integrity as the great majority of private firms routinely display.

… is from James Madison’s April 1787 memo, “Vices of the Political System of the United States,” which I first discovered long ago when reading William Lee Miller’s 1992 book, The Business of May Next: James Madison & the Founding:

Representative appointments are sought from 3 motives. 1. ambition 2. personal interest. 3. public good. Unhappily the two first are proved by experience to be most prevalent. Hence the candidates who feel them, particularly, the second, are most industrious, and most successful in pursuing their object: and forming often a majority in the legislative Councils, with interested views, contrary to the interest, and views, of their Constituents, join in a perfidious sacrifice of the latter to the former. A succeeding election it might be supposed, would displace the offenders, and repair the mischief. But how easily are base and selfish measures, masked by pretexts of public good and apparent expediency? How frequently will a repetition of the same arts and industry which succeeded in the first instance, again prevail on the unwary to misplace their confidence?

How frequently too will the honest but unenlightened representative be the dupe of a favorite leader, veiling his selfish views under the professions of public good, and varnishing his sophistical arguments with the glowing colours of popular eloquence?

Jim Buchanan often said that his and Gordon Tullock‘s work in public-choice and constitutional economics is, at bottom, little more than an elaboration upon, and a modernizing of, the political realism of America’s founders, especially that of James Madison.

One of the flaws of the modern punditry – and, more generally, of what Deirdre McCloskey calls “the herd of independent minds” – that I find most distressing is its refusal to be cured of its cancerous romanticism about government and coerced collective actions. Faith that some Great Man or Great Woman or Great Council – faith that some secular savior or saviors – can be found or fashioned to exercise power selflessly and in ways that, We are promised, will improve upon the realities of free markets and other venues of voluntary human interactions is an unshakable conviction among far too many elite pundits and intellectuals (who, amazingly, fancy themselves to be reality-based and science-driven).

… is from page 59 of the manuscript of Deirdre McCloskey‘s forthcoming volume, The Treasured Bourgeoisie:

Rhetoric matters just as much in the assaults on economic or political liberty as it does in their defense. The aristocracy or the country club favors a nationalist rhetoric nurturing military power, and a version of neo-aristocracy, in the name of King and Country. For a moderate showing of such tendencies in the United States see any Republican Party national convention. The progressive Christians or the herd of independent minds favors a socialist rhetoric nurturing the leading members of the Party and selected trade unions, in the name of the wretched of the earth. For a moderate showing of such tendencies in the United States see any Democratic Party convention.

Sheldon Richman recommends some excellent Memorial Day reading.

Doug Bandow ponders IRS reform.

My Mercatus Center colleague Veronique de Rugy reflects on Uncle Sam’s subsidy to Tesla Motors.

I share David Henderson’s positive assessment of a recent essay by John Allison.

This short post by James Hamilton is a good intro to Carmen Reinhart’s and Kenneth Rogoff’s defense of their research, defense of the applications they’ve made of their research, and defense of their integrity against what Hamilton appropriately calls “careless mudslinging” by Paul Krugman and others.

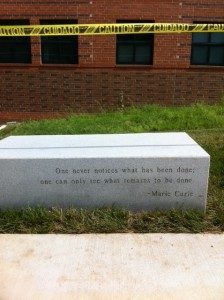

A major renovation of one of GMU’s science buildings is nearly complete. This building is next-door, on the Fairfax campus, to Enterprise Hall – home of GMU’s Department of Economics. Yesterday, when showing Methinks and her husband around campus, I snapped a photo of one of the brand-new stone benches that have been installed to line a walkway. Each bench features an inscription, such as…

Note that Madame Curie’s insight – “One never notices what has been done; one can only see what remains to be done” – applies not only to the narrowly scientific endeavors that she undoubtedly had in mind, but also to the economy.

The market economy works with such marvelous success at enriching every one of its denizens – enriching every denizen, to be precise, compared to the pathetically poor material standard of living each denizen would endure in the absence of market institutions – that we denizens of a market economy don’t ‘see’ the market’s abundant benefits. A fact both ironic and potentially dangerous is the reality that the modern market’s vast and largely silent (because its operation is usually so smooth) productiveness blinds people to the splendid reality of the market – which is to say, blinds people to the awful reality of what life would be like in the absence of markets (or what life would be like if markets were significantly more hamstrung than they are today).

We don’t notice what has been done. We don’t notice, at least not readily enough, often enough, and with enough historical knowledge.

The market distorts our perspective on what the market itself achieves. If there’s any feature of the market that warrants being described as “failure,” this distortion is it.

As I’ve written elsewhere, the demand for government intervention into markets – like the wealth that protects us from being seriously impoverished by such intervention – is a function not so much of the kinds of “market failures” (such as smokestack emissions) that economists feature in their textbooks as of, instead, the continuing stream of market successes that give people the mistaken impression that whenever the economy falls short of imagined ideal states a real problem is at hand, a problem that has a “cause” that can easily enough be cured by smart people with lots of power.

… is from page 123 of the 1981 Liberty Fund edition of Herbert Spencer’s important 1884 tract, The Man Versus the State:

The great political superstition of the past was the divine right of kings. The great political superstition of the present is the divine right of parliaments.

… is from page 175 of William Easterly’s brilliant 2001 book, The Elusive Quest for Growth:

Technology is a wonderful thing, but let’s not anoint it as yet another elixir for growth. Technology responds to incentives, just like everything else. When technology exists but the incentives for using it are missing, not much will happen. The Romans had the steam engine, but used it only for opening and closing the doors of a temple.